When we first started to write about the virus that causes COVID-19, my colleagues and I often referred to it as "the novel coronavirus." Its technical name is SARS-CoV-2, but that's hard to say and even harder to remember. And it was a novel coronavirus -- one which we initially knew little about. We didn't know how it spreads, or exactly how it causes the acute respiratory distress that leaves some sufferers gasping for air.

Now researchers at Stanford Medicine, including former instructor of allergy and immunology, Ivan Lee, MD, PhD, otolaryngologist Jayakar Nayak, MD, PhD, and microbiologist and immunologist Garry Nolan, PhD, have traced the path of infection from the time the virus latches onto cells in the nasal passages through its seemingly inexorable march to the lungs.

In doing so, they uncovered a possible reason why smokers infected with the virus are significantly more likely than nonsmokers to develop severe disease. They published their findings in October in Cell Reports Medicine.

Tracking the path of infection that leads to COVID-19

About a year ago, I wrote about how Lee, Nayak and Nolan showed that SARS-CoV-2 primarily infects ciliated cells in the upper airway. The rhythmically beating, hairlike projections of these cells move mucous and debris out of the airway. They are also a prime landing spot for the virus, which recognizes and binds to a protein found at high levels on the cells' surfaces.

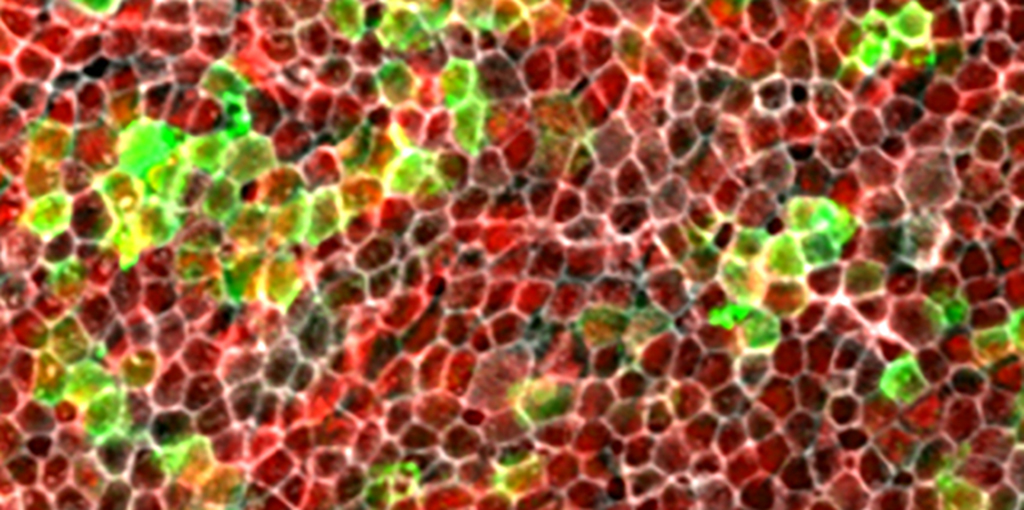

In the researchers' latest study, they and their colleagues from institutions around the world collected tissue samples from the nose, trachea, mouth and lungs of people who had died of COVID-19 early in the pandemic. They then analyzed these samples using several imaging techniques to quantify the receptors and the levels of viral genetic material. They used this information to determine the susceptibility of distinct mucosal surfaces in the human airway to viral infection.

"Based on our findings, we hypothesize that SARS-COV-2 infection typically starts in the lining of the nasal cavity and sinuses, and progresses from there into the throat, and ultimately the lower airways of the trachea and lungs," Nayak said. "Viral particles in nasal secretions are also carried from the nasal cavity into the mouth."

Notably, the researchers found that viral materials were most abundant in the nasal cavity and trachea (a part of the throat) in people with COVID-19, suggesting that the nose is the major route of transmission.

Unraveling the effects of smoking on COVID-19 severity

When they compared the levels of virus in the respiratory tissues in nonsmokers to those of smokers, the researchers found something interesting.

"We did not find that the SARS-CoV-2 entry factors studied in this paper were expressed at higher levels in the tissues of smokers," Nayak said. "This likely explains epidemiological data suggesting that smokers may not be at a higher risk of initially contracting COVID. Our data suggest however, that those smokers who do became infected are more likely to have severe disease due to reduced levels of an antiviral molecule, called interferon beta, in their upper airways."

Interferon beta is a type of molecule called a cytokine. Cytokines are key signaling molecules that regulate how immune cells grow and respond to threats like infection. Cigarette smoke has been shown in previous studies to reduce the signaling ability of some interferon molecules.

Lee and Nayak, in collaboration with researchers in the laboratory of immunologist Peter Jackson, PhD, to found that laboratory-grown human nasal tissues that were exposed to cigarette smoke were more susceptible to infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus than those that were not exposed to smoke. And adding extra interferon beta to the dish before exposing the cells to the smoke prevented infection with the virus.

"These findings highlight the central role of interferon beta in mediating susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in smokers," Lee said.

The researchers agree that whether you're a smoker or not, their findings point to the importance of masking to decrease your chances of inhaling viral particles. They also suggest a potential benefit of delivering vaccines or therapeutics directly to the nose to interfere with the earliest stages of infection.

Risky research

As the pandemic wears on, we're learning ever more about our viral foe. But conducting experiments to get the answers we need can still be tricky. Getting the tissues needed for this study, which represents one of the largest of autopsied human tissue obtained from COVID-19 patients, was challenging, the researchers said. It required the collaboration of many researchers.

"These dedicated physician-scientists assumed significant personal risk to undertake tissue sampling of proximal airway and head and neck sites in patients who had recently passed away from active COVID-19 disease, at a time when very little was known about SARS CoV-2, or about the effectiveness of masks and personal protective equipment, and when vaccines were not yet available," Lee noted.

The study also required family members to give permission to collect their loved ones' tissues.

"We are so grateful to the deceased individuals and their families for the generosity of tissue donation to help us better understand COVID-19 through research," Nayak said.

Photo courtesy of Ivan Lee and Jayakar Nayak