Being inches away from one of the world's deadliest viruses can give you a new perspective on things. Nipah virus, for example, is so dangerous it kills roughly 60% of the people it infects -- a whopping 100 times more than does SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Some Nipah outbreaks are 100% fatal.

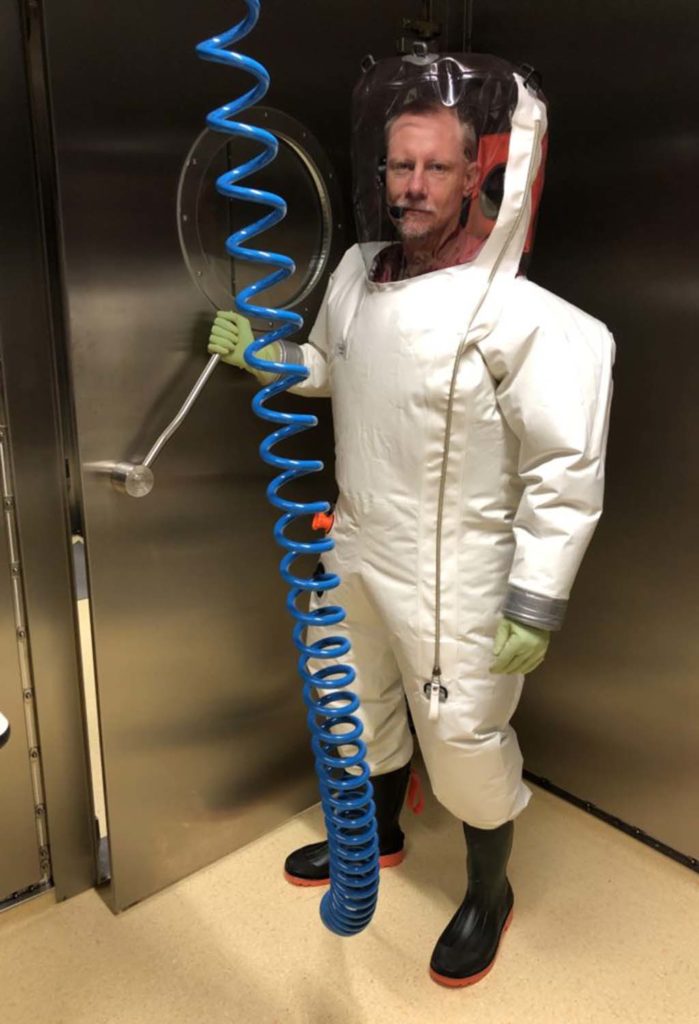

That's why the Nipah virus must be handled only in biosafety level 4 (BSL4) labs that provide the highest level of biosafety, including custom-made, full-body "space suits" donned by scientists. Specialized facilities are required so that deadly viruses are contained. In the lab, airflow is carefully monitored, and researchers breathe a separate, filtered supply of air.

Stanford Medicine scientists, in collaboration with the Robert Koch Institute in Germany, have been using stem cell science to investigate how Nipah virus infects and kills cells. Answers to these questions will be valuable if and when another Nipah virus outbreak occurs.

In research published June 22 in the journal Cell, Loh and his colleagues reported new information about how Nipah virus attacks blood vessels. Kyle Loh, PhD, assistant professor of developmental biology at Stanford, and Joseph Prescott, PhD, from the Robert Koch Institute, are co-senior authors on the paper.

Lay Teng Ang, PhD, an instructor and Siebel Investigator at Stanford's Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, and former Stanford research professionals Alana Nguyen and Kevin Liu, are co-first authors.

A top global health threat

There are many deadly viruses, of which Nipah is among the most infamous. Because there are no approved treatments or vaccines for Nipah, the World Health Organization has designated it as one of nine priority diseases that imperil global health.

The virus first emerged during an epidemic in 1998-1999 in Singapore (where Ang is from) and Malaysia, and it causes outbreaks almost every year throughout Asia.

In their research, Loh, Ang and their colleagues discovered how to create human blood vessel cells, such as arterial cells and human venous cells, in a Petri dish. To do so, they started from human pluripotent stem cells -- unique stem cells that can turn into any type of cell in the human body -- and methodically converted them into pure batches of blood vessel cells.

The research team then partnered with experts in blood vessel biology, including Stanford associate professor of biology Kristy Red-Horse, PhD, to show that blood vessel cells functioned like real blood vessels.

"It's amazing that when you grow these cells with the right signals, they develop into real arteries and veins," Ang said. "You put them in a 3D gel, and they automatically assemble themselves into the right structures."

Developing an early interest

As a kid growing up in New Jersey, Loh was drawn to the book The Hot Zone, about an Ebola outbreak and the BSL4 virologists who studied it. His father forbade the young Kyle to read the book, because he thought it was too scary for a 7-year-old. Loh read it in secret. "And then I took it to my second-grade classroom for show-and-tell," Loh said mischievously.

Years later, at a scientific retreat, Loh met Prescott, a global authority on Ebola, Nipah and other deadly viruses as well as deputy director of the Robert Koch Institute's BSL4 lab, one of the few BSL4 labs worldwide capable of studying these deadly viruses.

"The air pressure in the labs is less than outside air, so nothing escapes. There are airlocks and detailed decontamination procedures for getting in and out," said Prescott, noting that security procedures for accessing the lab are classified and equipment cannot be removed. "BSL4 labs are like the Hotel California -- scientific equipment can go in, but it never leaves."

How these deadly viruses attack blood vessels, which are found in and nourish all the organs in the human body, is largely a mystery, said Prescott, because autopsies are rarely performed on human victims. "It's too dangerous. Besides, autopsies would show only the end stages of the disease."

Nipah's destructive forces

The only way to study how Nipah infects and attacks human cells is to infect living human cells in a dish, which was possible once the Stanford team discovered how to create those cells for research.

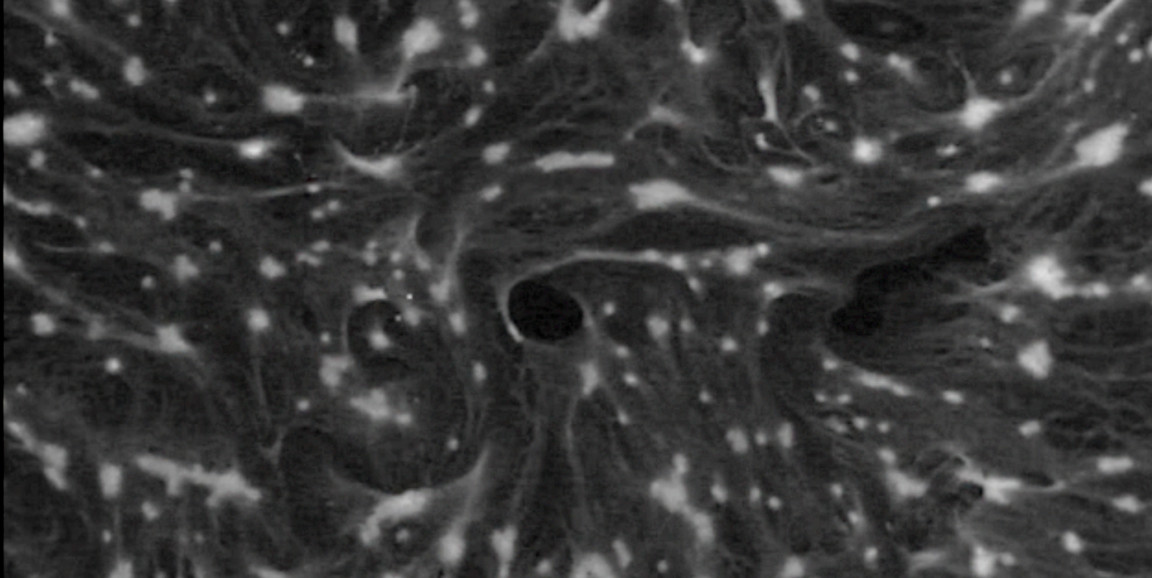

When Prescott exposed arterial and venous cells to the Nipah virus, the results were frightening. In a video published with their Cell paper, the scientists showed how arterial cells (but not venous cells) infected by the virus undergo, as Ang puts it, horrifying changes.

"What the Nipah virus does is fuse individual arterial cells into massive, swollen super-cells containing the contents of many individual cells. All the cell nuclei are drawn together into a clump, like a cluster of grapes," Ang said. "Then the arteries just disintegrate."

The veins, however, are unscathed, perhaps because the veins lack a cell receptor known to play a role in the entry of the Nipah virus into cells. This information could ultimately help devise ways of preventing Nipah from infecting cells, Ang said.

One of the greatest research surprises came after the Nipah virus entered an artery cell and rampaged through it, forcing it to fuse with its neighboring cells: The cell was almost completely unaware of what was happening to it. Normally, cells infected with viruses set off alarm bells, rousing proteins to combat the incoming virus.

However, even after the Nipah virus took over the cell's machinery (so much so that 17% of the genetic material in the cell was produced by the virus), Nipah-infected artery cells went about their business as if nothing was wrong.

"We think of Nipah virus as a stealth bomber," Loh said. "The virus sneaks into the cell under the radar and drops its bombs undetected, with the cell unable to tell that the virus is there and powerless to fight back."

The research team believes that stem cell science can take the field of virology in new directions, and that the ability to create human cells from stem cells can provide a more realistic system to study how BSL4 viruses infect human cells as well as discover effective therapies.

More Stanford scientists are undergoing training to conduct research in the Robert Koch Institute BSL4 lab and partner with scientists at the institute to study other deadly viruses -- including Ebola -- in the hopes of better preparing for future outbreaks.

Top photo courtesy of the Robert Koch Institute-Berlin