People don't go into Michael Angelo's field to be cool.

"Pathology is like the chess club of medicine," said Angelo, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of pathology at the Stanford School of Medicine. You don't join for status -- you join because you love it, he said.

Still, Angelo got the idea for a pretty cool technology when he was a young pathology resident studying the origins and trajectory of disease.

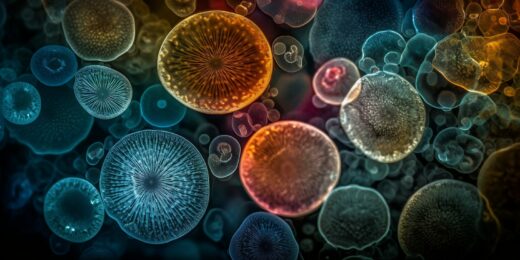

For decades, clinicians have diagnosed and assigned treatments for tissue-bound cancers by identifying a handful of culprit molecules, typically proteins, near a patient's tumor. But Angelo's technique, which blasts patient samples with ions to reveal proteins in disease-relevant cells, could help clinicians detect more than 40 different molecules at a time. That kind of leap in quantitative detection opens the door for more personalized care, Angelo said, as the type and location of proteins and cells in a person's tissue hints at the underpinnings of their specific disease, and therefore which treatments might work best.

Scientists searching for details of a patient's cancer typically perform something called staining, during which they bind fluorescent tags to proteins of interest in tumor cells so they glow under a microscope. But scientists can only image as many proteins as there are detectable colors. That means clinicians must predict the cell abnormalities driving cancer -- and effective treatments -- with limited information. At the beginning of his pathology career, Angelo was struck by this quandary. He noticed that while new technologies probed for multiple disease markers in blood samples, tissue-bound tumors still relied on staining.

"It was like the technology went back in time 40 years," he said. Along with other Stanford Medicine scientists, in 2018, Angelo developed a technique that broadens scientists' detection capabilities -- and sounds like science fiction. It's called multiplexed ion beam imaging by time of flight (MIBI-TOF), and it works by harnessing dozens of unique metals that are rare in the human body, attaching them to proteins of interest, and blasting them with ions to reveal their location in a tissue sample.

The ion beam strikes the sample and launches tissue particles into the air; imaging software then detects them and traces the particles to their original location. Because there are many more metals than there are colors (over 50), the technology enables scientists to amplify the number of detectable proteins.

"We're looking at things more at a systems level," Angelo said. "That's been missing in pathology."

Predicting breast cancer

Angelo and a team of researchers at Stanford Medicine recently employed their technique to better understand an early form of breast cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ. "This type of breast cancer isn't typically life-threatening," Angelo said. It needs to spread and become invasive breast cancer to be dangerous.

About 55,000 women are diagnosed nationally with this precursor each year. But it's hard to tell which of these cases will advance and which will not. Consequently, most of these patients receive treatment, even though up to half of them would not have developed invasive breast cancer.

Angelo and his team think their technique can separate the high-risk patients from the low-risk ones and help personalize care plans by determining specific proteins' locations and how they relate to the cancer's advancement. To test it, they used MIBI-TOF on nearly 80 breast tissue samples that had been stored in a biobank and found a molecular signature that predicted which patients would develop cancer within 10 years of their diagnosis with 74% accuracy.

Answering today's research questions with decades-old tissue

To determine the breast cancer risk signature, Angelo's team pulled historic tissue samples, some that were more than 30 years old, for analysis. When patients undergo tissue biopsies, samples are sometimes stored with their consent for research purposes. MIBI-TOF technology works on these banked samples, which is important, Angelo said. Banked tissues that have been treated with preservatives can be difficult to image using other existing technologies.

Being able to tap into archived tissue opens doors for new research, said Angelo. Because by law such tissues must be kept for at least 10 years, biobanks in pathology departments at academic medical centers typically house tens of thousands of samples. If a trainee comes to Angelo asking to study a specific type of cancer, he can easily find deidentified samples to examine with MIBI-TOF.

"No matter how obscure, I could probably have a cohort of 10 samples in a week," Angelo said.

Such studies open research opportunities because they don't rely on patients to donate more tissue. Scientists can predict their clinical outcomes using existing samples.

MIBI-TOF works well as a research tool and could one day be used routinely in clinical care. To get there, the technology must demonstrate it can simultaneously improve patient care and perform the functions of traditional staining, Angelo said.

Until then, Angelo will continue to run experiments to test MIBI-TOF's potential.

"I have no doubt that there will be great utility for this in terms of better diagnostic prognostic readouts and drug triage," he said.

Photo by Visual Generation