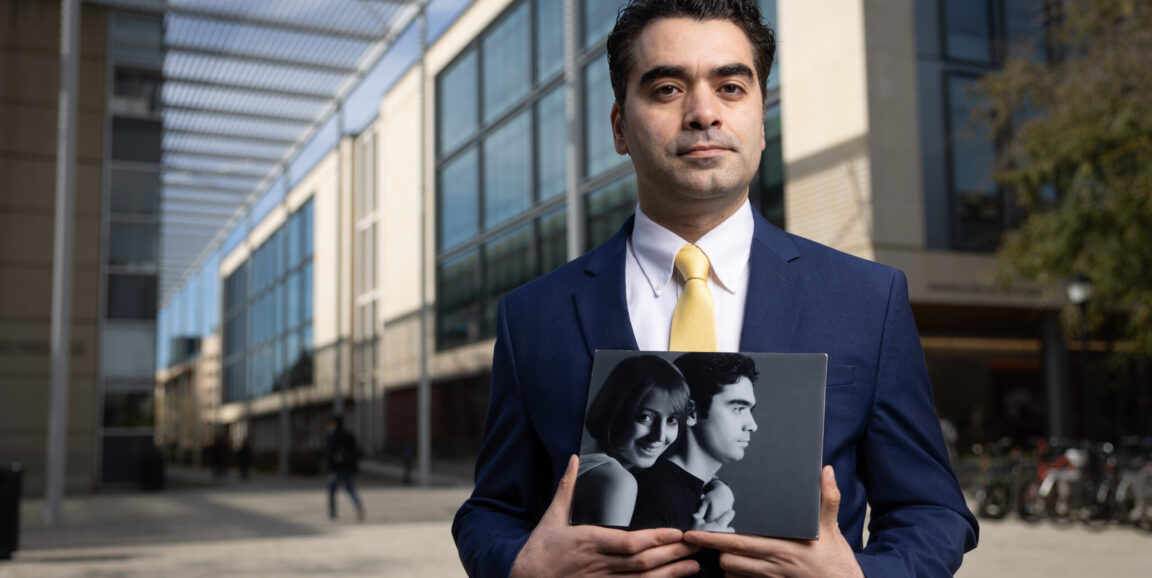

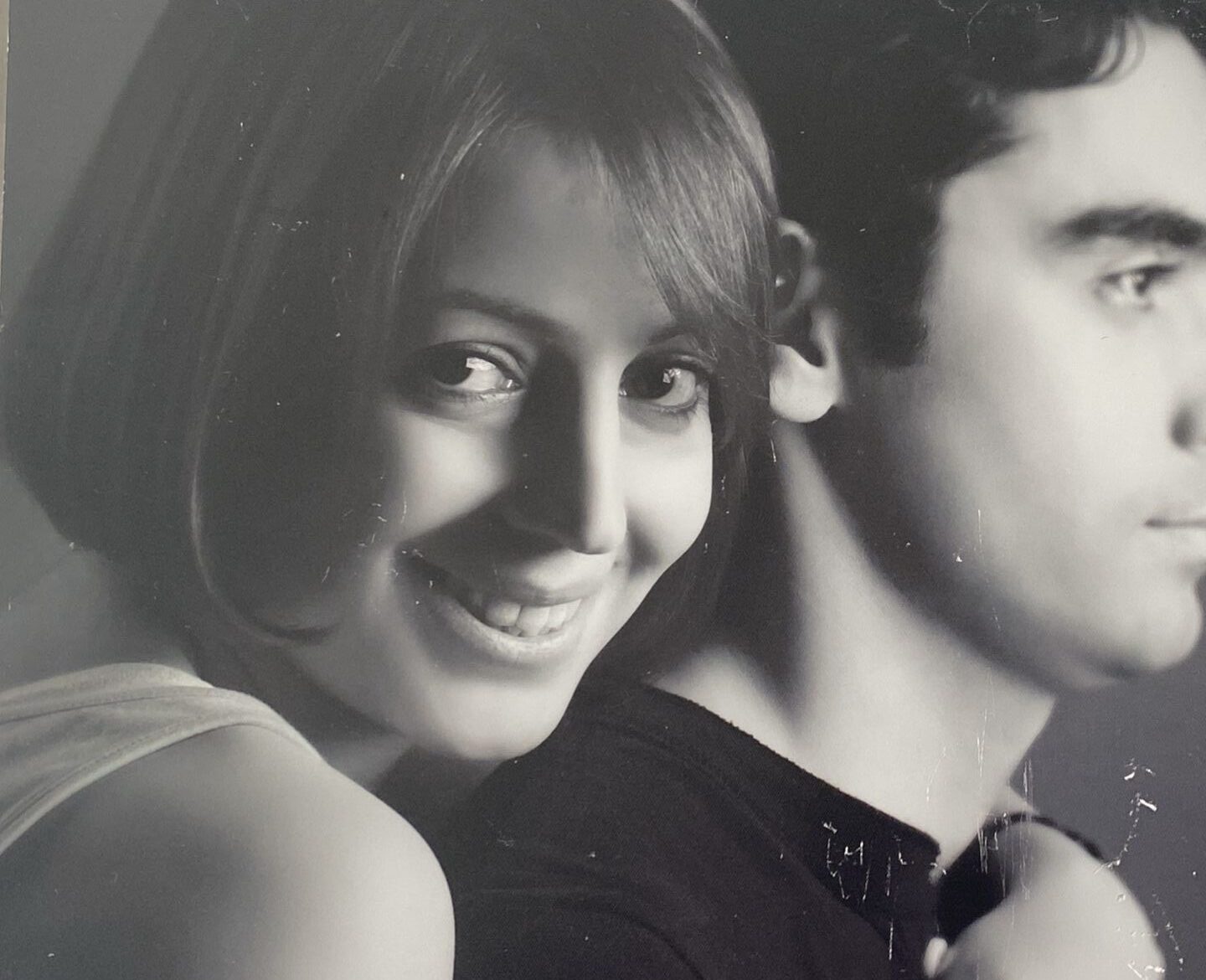

Amir Bahmani, PhD, reached a desperate low in his life following the death of his wife, Someyra, in 2014. Doctors mistook her terrible pain for an inflamed gallbladder, missing the signs of a malignant cancer.

"If they had collected the data, they would have seen that something was going on internally, that there was a big shift underway that occurs with cancer patients," said Bahmani, director of the Stanford Deep Data Research Center. "They might have been able to catch it early and give her a better chance."

In his grief, he realized how much data science could impact medicine and potentially save lives. That's when he resolved to help close that gap and bring the disciplines closer together for the sake of realizing a precision medicine approach -- the type that could have made a difference for Someyra.

"We want to create a common language between engineers, biologists and physicians," said Bahmani, a high-performance computer scientist. "We don't need to know everything, but we need to know enough to communicate efficiently with each other."

We don't need to know everything, but we need to know enough to communicate efficiently with each other.

Amir Bahmani

Bahmani was ready to dedicate his life to medicine. But, as an Iranian immigrant without financial means, he faced major obstacles. He had been the first in his class in Iran to obtain a fellowship abroad -- an almost unthinkable possibility -- obtaining a research fellowship at North Carolina State University, where he received a PhD in computer science.

And after battling to obtain visas, Someyra, whom he had met as an undergraduate, was able to join him as a research assistant in engineering at NC State. Together they dreamed of raising a family in America and creating a better life for themselves.

Then came the terrible side pains and suddenly a young husband's worst nightmare was unfurling before his eyes. Someyra was just 26 when she died.

But a grieving Bahmani couldn't have anticipated the challenges he would face in continuing on alone with their shared American dream. After he returned to Iran to bury Someyra, he said he narrowly escaped being drafted into the Iranian army and then also nearly lost his research fellowship because of delays in renewing his visa, which was held up by Iranian authorities.

"In six months, I lost everything. I lost my best friend -- my wife -- and now I was afraid I was going to lose my career," he said. Then, a stroke of good luck: He received a note from the U.S. Embassy in Armenia that his visa awaited him there.

Embracing the challenges

Back in the United States, more tests also awaited him. Bahmani's Iranian background prevented him from working with U.S. national laboratory scientists in high-performance computing. Fortunately, a mentor introduced him to researchers at the Duke Cancer Institute at Duke University School of Medicine.

That would lead him to his first big break: a $10,000 Amazon Web Services (AWS) grant through a program to fight cancer using cloud services, a cost-efficient method for storing and processing large quantities of data. He went on to collaborate with the Duke researchers to publish his first cancer research paper in 2015 on a rapid-fire statistical technique to associate certain cancers with specific mutations.

That introduction to genetics launched Bahmani on a fascinating, if difficult, course. As a computer scientist, the world of genetics seemed daunting. There was so much to be learned. He recalls hearing the term "messenger RNA" from his Duke collaborator early on.

I didn't know what (messenger RNA) was. It's scary when you are in a different field.

Amir Bahmani

"I didn't know what it was," he said. "It's scary when you are in a different field."

To expand his knowledge and embrace the challenge, he got an internship that summer at Illumina Inc., which builds computer systems for genetic analysis. He was hired at the Palo Alto, California, company the following year and then joined Stanford Medicine in 2017 as a biomedical data scientist working under the wing of Michael Snyder, PhD, the Stanford W. Ascherman, FACS Professor in Genetics and chair of the Department of Genetics.

That year, Snyder was able to self-diagnose Lyme disease before he had any symptoms by using a wearable device that showed measurable signs of an internal fight with a pathogen. Snyder published a major study on the process, which involved collecting massive quantities of data -- two petabytes, or two million gigabytes.

Bahmani said it was clear they needed a better way to store and process all that data so he turned to cloud computing to help build a system called My Personal Health Dashboard (MyPHD) that has since facilitated more than 30 research studies involving over 10,000 participants.

Using the technology, he and his collaborators -- including physicians, geneticists and computer scientists -- developed two algorithms to detect COVID-19 infection as much as seven or eight days before symptoms occur, based on internal changes in the body. They also devised a COVID-19 alert system to warn people early of a developing infection. That work was published in 2022 in Nature Medicine.

Educating with precision

Bahmani wanted to expand the community of people who could work on these complex, multidisciplinary problems. So, with Snyder's help, he developed a course, Cloud Computing for Biology and Healthcare, that included lectures by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and other luminaries in the field.

"I have always believed that in order to deliver precision medicine, we need to deal with precision education," said Bahmani, now a lecturer in the Department of Genetics. "If anyone around the globe wants to contribute to medicine, they should have a chance."

More recently, he has developed a new certificate program, Fundamentals of Precision Medicine and Cloud Computing, a self-paced curriculum on medicine, genetics and data science for high school, college and graduate students. It begins with lessons on data privacy and moves on to topics such as programming, statistics, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, medical imaging, genomics and wearable devices.

Bahmani is passionate about making these educational opportunities free to underserved students -- those with incomes less than $70,000 -- as he believes these trainees have much to offer the world of medicine.

Moreover, he wants to give back to a system where people like him -- an Iranian immigrant of modest background -- can thrive when given opportunities they wouldn't otherwise have. The program is offered through a nonprofit for which he is seeking additional support.

To truly build trust and establish inclusive healthcare systems, we need to prepare more researchers and experts from underprivileged communities.

Amir Bahmani

"To truly build trust and establish inclusive healthcare systems, we need to prepare more researchers and experts from underprivileged communities. We want different voices from different communities," he said.

In the process, he hopes to save more patients from the kind of missteps that took his wife from him.

"This is all done in her memory," he said. "Maybe we can avoid such tragedies for others by detecting these diseases much earlier."

Main image: Jim Gensheimer