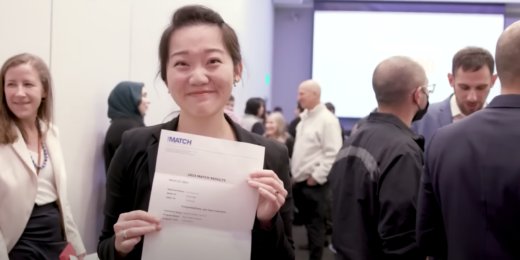

At exactly 9 a.m. Pacific Time on every third Friday of March, anxious graduating medical students around the country tear open envelopes to reveal where they matched for their residencies.

These three- to seven-year residency programs, usually based at hospitals, are essentially their first jobs out of medical school and the next stage of their training to become fully fledged and licensed physicians.

Match Day might sound like a combination of the Oscars and one of Harry Potter's Sorting Hat ceremonies, but it's the result of an algorithm to create the ideal pairings between tens of thousands of applicants and residency programs. Here's how it works.

What history tells us

The modern residency match originated in the 1950s to tame an increasingly chaotic system. Hospitals competing to hire the best medical students were offering positions earlier and earlier, sometimes locking in students who were only halfway through medical school.

When rules were made to limit offers to the fourth year, programs began pressuring students to accept or reject offers on shorter and shorter deadlines -- sometimes within 12 hours of an offer being sent by telegram. Hospitals scrambled to hire the top students while students tried to delay their decisions until they had all offers on the table.

Enter 'the algorithm'

In 1952, a centralized matching system -- which would become the National Resident Matching Program -- was introduced. Students submit a ranked list of their preferred programs, and the programs submit a ranked list of their preferred students. A mathematical algorithm then decides on the matches optimized for both parties.

The algorithm is designed to achieve stable matches, so that no student and program who were not matched together would prefer each other over their assigned matches. (Only students and programs that have ranked each other can match.)

"It's the most fair and equitable way to give everyone across the country an opportunity to participate and to see everything that's out there," said Nounou Taleghani, MD, PhD, the academic advising dean for the Stanford School of Medicine and clinical professor of emergency medicine.

Over the years, the algorithm has been tweaked to keep up with the times. Stanford economist Alvin Roth, PhD, helped redesign the current version in 1998, which takes into consideration new factors such as couples hoping to match in the same program or city and specialties that require two residencies. The current algorithm is "applicant-proposing," meaning it starts at the top of the applicant's rank list. Roth shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in economics for his work in market design.

How todays' match works

Medical students apply to residency programs in September of their final year. Over the subsequent few months, they are invited to interview by some of the programs.

The number of programs that students apply to can vary depending on the competitiveness of their specialty. For example, in this year's match, students applying to pediatrics residencies submitted an average of 44 applications and those applying to surgery residencies submitted an average of 70 applications.

Since the pandemic, residency interviews that used to require travel can now take place online, and students have applied to and interviewed at more programs. Students can rank only programs they've interviewed for and vice versa.

Prior to Match Day, students and programs are banned from communicating their preferences to each other with one possible exception: Students can indicate their inclination to the program they intend to rank first.

"A program can't call a student and say, 'We're planning to put you down as No. 1. Are you going to put us down as No. 1?'" Taleghani said. Such communications are considered a match violation.

By early February, students and programs submit their ranked lists to the National Resident Matching Program, which runs the data through the algorithm -- and then the wait begins.

On the Monday before Match Day, students are notified by email whether, but not where, they have matched. This allows those who have not matched to quickly apply to unfilled positions over the next few days in what's known as the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program. The final matches are revealed on Friday at the Match Day ceremony and simultaneously by email.

Match Day by the numbers

42,952: In the 1952 residency match, just 6,000 students applied for 10,400 positions. In 2023, 42,952 students vied for 40,375 positions in nearly 50 specialties.

81.1%: The overall percentage of applicants -- including international applicants -- who matched last year, though rates vary among specialties, ranging from rates in the 60% range for plastic surgery and orthopaedic surgery, to above 97% for pediatrics, emergency medicine and internal medicine.

98%: The number of Stanford Medicine students who typically match each year. "The overwhelming majority of our students match, and a lot of them get their first choice," Taleghani said.

Advice to students

The National Resident Matching Program advises students to rank according to their true preferences even if they think they have little chance of matching at their top choices: "The matching algorithm attempts to place you in the most preferred program possible, so be sure to rank programs in order of your true preference and not where you think you will match. Go for your 'reach' program."

In a computational study of the algorithm, Roth concluded, "Both applicants and programs can be safely advised that, at the point in the process when they decide what Rank Order Lists to submit, they are extraordinarily unlikely to be able to influence the outcome of the match in their favor by submitting a list different from their true preferences."

Conversely, students should not rank any program they are unwilling to commit to because the match is considered a contractual agreement, Taleghani said. "If they match there, they have to go."

Taleghani still remembers vividly her own Match Day nearly 30 years ago. "I remember walking up to the dean and getting the envelope and opening it. It's as if it was yesterday," she said.

"The event is that memorable for everyone because it is the culmination of all that hard work."