While artificial intelligence chatbots are getting better at mimicking humans, they aren't always developed with medicine in mind. That's why Stanford Medicine doctors and researchers are modifying existing chatbots to perform well in a frontier of AI-enhanced medicine: the doctor-patient interaction.

These efforts to help physicians care for patients more efficiently, without compromising accuracy, could help guide how AI enters the doctor's office in the years to come. Researchers endeavored to make models that doctors could rely on to accurately document patient history or answer medical questions -- and keep data secure.

"I'm really excited for what the field will do over the next three to five years," said Thomas Savage, MD, clinical assistant professor of medicine. But his excitement comes with an important caveat: "We have to be really careful about how we end up using these tools," he said.

Stanford Medicine researchers recently conducted three studies testing large language models in medicine. One created a chatbot to help doctors more quickly and easily search the latest treatment plans before writing prescriptions for patients. Another found that AI models could efficiently produce medical summaries as good as or better than a doctor could. Savage's team wondered if AI models could mimic a doctor's thought process in making a diagnosis.

Doctors 'Ask Almanac'

Doctors can't be expected to know everything. That's why they use resources such as PubMed and BMJ Medicine to search for the most current information on treatment plans, diseases and diagnoses.

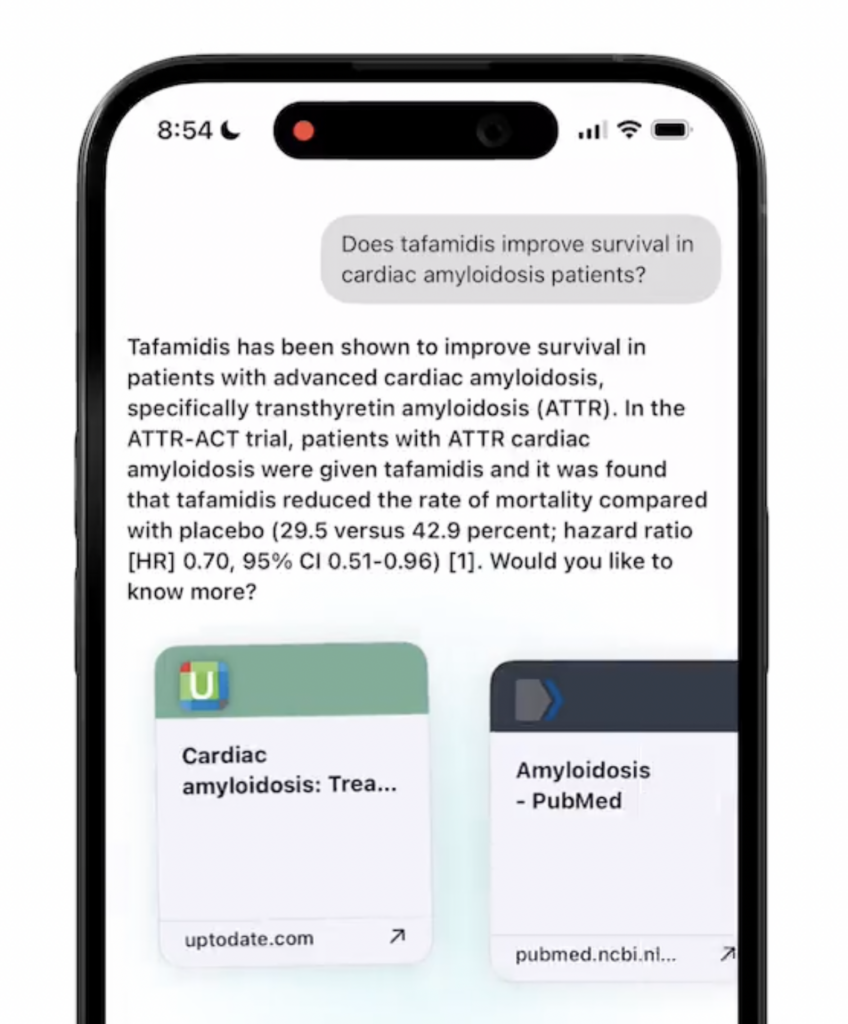

But recent medical school graduate Cyril Zakka, MD, believed that AI could make that process better. That's what gave him the idea to create Almanac, a search engine that guides chatbots to reputable sources to answer open-ended physician questions.

Zakka said with Almanac, doctors could decrease their search time from 5 to 10 minutes to roughly 14 seconds. "That accumulates," said Zakka, who is now a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford Medicine. "My goal is not to replace physicians, but to help them get through their day."

Along with an answer to their question, Almanac cites where it retrieved the information so doctors can fact-check it. Zakka said other similar language models are being trained and tested on medical school exam questions, which can be over-simplified and out-of-date. On the other hand, doctors on Zakka's team tested Almanac on questions more reflective of their day-to-day practices, which Almanac was able to answer based on the most up-to-date medical guidelines.

Recently, Zakka and a physician-led team compared Almanac with other popular language models. The panel preferred Almanac's answers over the others, finding them to be significantly more factual and complete. He said Almanac also offers better security against cyber-attacks because it won't reply to a doctor's question if it detects its been corrupted to output information that's potentially incorrect or harmful Zakka and team reported those findings Jan. 25 in NEJM AI.

"Several companies have reached out and already implemented Almanac," Zakka said. "Physicians at Stanford and abroad are pretty excited."

Next, Zakka is building a version of Almanac, called Almanac Chat, that can help doctors interpret images and video of different medical conditions. He hopes the updated chatbot will serve as a physician's co-pilot.

"This isn't the final version," Zakka said. "But we're working toward it."

An answer to workload burnout?

Physicians often feel they spend too much time writing and not enough time with their patients. A 2020 study found they spend nearly half of their work time on electronic health records. With so much on their plate, Dave Van Veen, a graduate student at the School of Engineering, wondered if AI could help lift the load.

"I wanted to make the clinicians' lives easier," said Van Veen, who is shadowing doctors at Stanford Hospital for his graduate thesis, "so they can spend more time on direct patient care."

He wondered if he could adapt existing large language models to summarize clinical text as well as physicians do. Along with collaborators, he adapted eight different models to summarize tasks such as doctor-patient conversations and progress notes. Then, a panel of 10 physicians evaluated the models' summaries for thoroughness, accuracy and brevity.

Van Veen was surprised to see that the best-scoring models performed as well as or better than human experts at writing summaries. The findings were published Feb. 27 in Nature Medicine.

"We were hoping to show that these models are about on par with clinicians," Van Veen said. "We were really astounded to see that they actually outperform medical experts for these tasks."

We were really astounded to see that they actually outperform medical experts for these tasks.

Dave Van Veen

Van Veen's advisor, Akshay Chaudhari, PhD, assistant professor of radiology, said the adaptations Van Veen designed to coax the models to write summaries was critical to their performance. Also, on average, the physician panel thought that if the computer-generated summaries were used directly, they would have comparable likelihoods as human summaries to cause harm, such as a misdiagnosis or injury.

Ideally, Van Veen said, the AI and humans would work as a team. The adapted models, the researchers hope, could reduce physician stress by helping them summarize reports more quickly and with less cognitive stress. The physicians would also review the model's summaries for accuracy.

Next, Van Veen will work alongside clinicians to gauge how adapted models could be integrated into their workflow. Then he hopes to test the models in clinics to see if offloading summaries effectively reduces stress and burnout for doctors.

Can models help doctors make a diagnosis?

Savage, a physician and professor, often listens as medical students and residents recount how they arrived at a patient diagnosis.

Their diagnosis is more likely to be accurate if the trainees use a certain process and line of reasoning, Savage said. For example, medical students are trained to open their minds to all possible diagnoses before narrowing them down.

Savage wondered if large language models could be taught to reason like doctors, and if such thought processes would improve the accuracy of their diagnosis. Along with a team of Stanford Medicine researchers, he prompted the generative models, GPT3.5 and GPT4, to answer open-ended medical questions, using both traditional reasoning, which broke the task into small logical problems and solved them step by ste , and reasoning that mimicked a clinician's thought process.

The models' answers were evaluated for accuracy by four physicians, including Savage. They found that GPT 3.5 had worse accuracy when using clinical reasoning strategies, while GPT4 tended to have similar accuracy, whether it used traditional AI-type reasoning or reasoning that modeled human thought. Their findings were published Jan. 24 in npj Digital Medicine.

Our interpretation was that language models can't think like a physician can, but they're getting a lot better at mimicking that thought process.

Tom Savage

"Our interpretation was that language models can't think like a physician can, but they're getting a lot better at mimicking that thought process," Savage said.

The idea is that if models like GPT4 and its successors can present diagnostic reasoning like a human would, without compromising accuracy, doctors like Savage could more easily double-check their findings, similar to evaluating the reasoning of a medical student or resident. Any diagnostic conclusions made by a model will need to be confirmed by a doctor, Savage said. So, naturally, it would be helpful to have the model's conclusions presented in a familiar format.

Next, he's evaluating ways to assign a numeric uncertainty level to model answers, to tell clinicians how confident they can be that a response is accurate. Eventually, Savage thinks chatbots will be ready to ask patients about their history and present plausible diagnoses to a doctor. But the doctor will always be in the driver's seat - they'll just be in possession of another tool.

"We have to find areas to deploy them where they're going to have benefit, but also present low risk," Savage said.

The latest news on medicine & AI

- AI assists clinicians in responding to patient messages at Stanford Medicine

- Ambient artificial intelligence technology to assist Stanford Medicine clinicians with taking notes

- AI's future in medicine the focus of Stanford Med LIVE event

- AI explodes: Stanford Medicine magazine looks at artificial intelligence in medicine

- How Stanford Medicine is capturing the AI moment

- AI experts talk about its potential promise, pitfalls at Stanford Medicine conference

Image: Ground Picture