In his nearly two decades as a clinical professor at Stanford Medicine, Bryant Lin had never stood before a classroom of students as a patient -- let alone as a patient who, despite never inhaling "a single puff of smoke of any kind," has been afflicted with an incurable form of late-stage lung cancer.

Therefore, it was little surprise when the focus of lesson No. 1 in his new fall class swerved toward Lin's tear ducts rather than his lungs.

"I was hoping not to get choked up... but somebody, thoughtfully, left a Kleenex box up here," Lin said, reaching toward the nearby podium of a unique class he named MED 275: From Diagnosis to Dialogue: A Doctor's Real-Time Battle with Cancer.

It was in early May, about a month before his 50th birthday, that he received the diagnosis of stage IV non-small cell cancer -- aka never-smoker lung cancer.

To encapsulate for the students what drove him toward medicine, Lin began to read aloud a handwritten letter he received from an elderly patient with chronic kidney disease many years ago.

"Dear Dr. Lin: I wanted to thank you for taking such good care of me in my old age. You treated me as you would treat your own father, with humor and care and great professional skills."

That letter arrived two weeks after the man's death ... which means that he spent time in his final hours writing a letter for me.

Bryant Lin

"That letter arrived two weeks after the man's death ...," Lin said, his strong baritone voice now soft and crackly. "Which means that he spent time in his final hours writing a letter for me."

As he spoke, the doctor-turned-patient stood before a small classroom at Li Ka-shing Hall that was overstuffed with people. Many among them were trying to control the commotion stirring in their own tear ducts.

"I'm not sure how long I have. One year? Two years? Five years?" Lin told the group. "In a way, this class is part of my letter -- what I'm doing to give back to my community as I go through this."

A no-brainer decision

A longtime caretaker of very ill patients, Lin, MD, a primary care physician, educator and researcher, is now discovering what it's like to be on the opposite end of that arrangement. He admits that it can be difficult: "Doctors are notoriously bad patients," he said.

He is a sharer and storyteller by nature, which explains why the man who directs Stanford Medicine's Medical Humanities and the Arts program decided quickly after he was diagnosed to turn his own experience into a real-time living laboratory to be observed; processed; and, he hoped, learned from.

To Lin, it was simple logic: If medical students, and the greater Stanford School of Medicine community, can take something valuable from his fight against the deadliest form of cancer, the remainder of his life will have served a meaningful purpose.

"It's an honor you would want to sign up for my class," he told the mix of Stanford School of Medicine medical students and Stanford University undergrads. "My dream is that you will go into cancer care. It would be great if even just one of you dedicated some part of your career to cancer."

It's an honor you would want to sign up for my class. My dream is that you will go into cancer care. It would be great if even just one of you dedicated some part of your career to cancer.

Bryant Lin

Particularly, Lin noted, researching elusive cures and pushing for more widespread screening. As one of the world's experts on diseases that disproportionately affect people of Asian descent -- the Taiwanese-American Lin co-founded Stanford Medicine's Center for Asian Health Research and Education in 2018 -- he knows the stark data points.

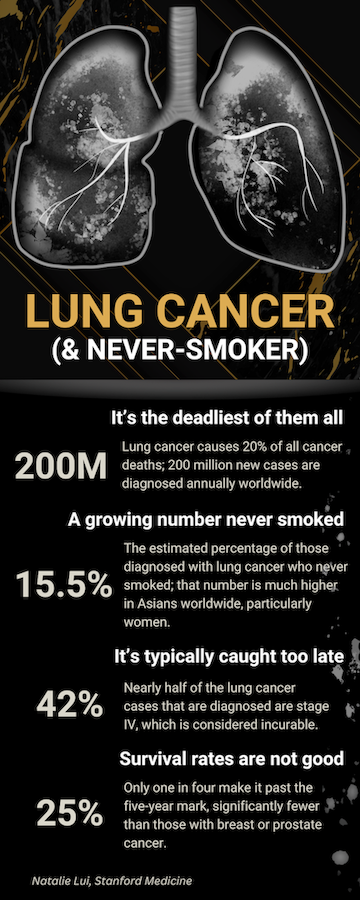

Though prostate (in men) and breast (in women) are the most prevalent forms of cancer, more people die from lung cancer than any other form. Some 200 million worldwide receive a lung cancer diagnosis each year. An estimated 125,000 people in the U.S. will die from it this year.

While smokers make up the majority of those cases, 15-20% of people with lung cancer are like Lin and never took a puff. Instead, like Lin, their plight is the result of a gene mutation that disproportionately affects those of Asian descent, particularly women.

So why is the survival rate for lung cancer so stark? There was a lesson for that on day one of MED 275. And Lin selected his colleague Natalie Lui, MD, a thoracic surgeon who runs the lung cancer screening program at Stanford Medicine, to lead it. As Lui spelled out, lung cancer is largely a silent disease that goes undetected for a dangerously long period.

"It doesn't cause symptoms until it's quite advanced," Lui explained. "And if someone goes to their primary care doctor and says, 'I have a cough,' it could be a million different things other than lung cancer. So, it's really hard to diagnose people early -- and the prognosis plummets with the later stages it's detected."

Lin's primary care doctor, Paul Ford, MD, illustrated how that scenario played out in Lin's lungs, showing the class slides of the imaging that led to the diagnosis: X-ray, MRI, CT and PET scans. The MRI revealed cancer that had metastasized in his liver and bones. Most striking were the number of lesions on his brain. "Fifty spots of cancer on my brain ... that kinda blew me away," Lin said. "That drove it home."

Inspiration 101

Longsha Liu, a medical student and one of three volunteer teaching assistants, refers to MED 275 as a "once-in-a-lifetime class." He said Lin helped mentor him as a budding medical entrepreneur, generously sharing his time and wisdom on how he balances what would seem to be impossible: teaching students, maintaining a clinical practice and launching successful companies.

"To watch someone you really admire see their fate change so quickly is a very helpless feeling," Liu said. When he asked Lin how he could help, Lin told him about the class and asked him to be a TA. It was a done deal and little surprise, Liu said, that the class quickly filled and drew an immediate waiting list, and that they had an overflow crowd problem for the very first gathering.

"Here's a guy diagnosed with cancer and what does he immediately think of?" Liu said. "'How can I help others by sharing this journey?'"

Here's a guy diagnosed with cancer and what does he immediately think of? 'How can I help others by sharing this journey?'

Longsha Liu

Sasha Ronaghi is close to completing her Stanford undergraduate degree in computer science, but she won't pass up an interesting class when she sees one. Though she has no plans to go into medicine, she has become a regular in front of the room after classes, waiting to ask Lin additional questions.

"We all know someone who has experienced cancer, but we wish we could understand that experience better," she said. "What really struck me was when Dr. Lin said that his life hasn't changed since his diagnosis. Even now knowing that he has a limited time on earth, he was already doing the things he loved. That's inspiring, and it helps guide me as I get close to graduating and figuring out my next steps in life."

For first-year med student Melissa Maldonado Ogle, with an interest in both the equity of global oncology treatment and the humanistic side of medicine, Lin's class could not have been more on target. Getting into the course was like finding a golden ticket.

"I feel so fortunate to have gotten in," she said. "For someone to have the bravery and vulnerability to do a class like this, I just thought it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity."

"We focus a lot on therapeutics and science, and sometimes we forget that there's a human being on the other side of it," Maldonado Ogle added. "To hear Dr. Lin's human perspective, then look at it from an epidemiological level, really helps contextualize the conversations we're having."

A full cancer slate

Though Lin's journey is only five months old, the syllabus he mapped out for the 10-week course runs the full cancer gamut: the mental health impact; the role of caregivers; how spirituality, ethics and nutrition factor in; the access and availability of treatment; what the epidemiology says about cultural considerations such as genetic predisposition.

Speakers will include his wife, Christine Chan; his oncologist, Heather Wakelee, MD; and a spiritual panel that includes representatives from four different faiths: Buddhism, Hinduism, Catholicism and Islam. The final class, after the Thanksgiving break, will explore cutting-edge advancements in cancer treatment, including CAR T-cell therapy, antibody-drug conjugates and next-generation drug inhibitors.

The latest generation of drug inhibitors -- combined with chemotherapy -- have Lin feeling pretty well. Those 50 lesions on his brain are gone. As is the deep, angry cough that started this whole journey back in May when students and colleagues around him assumed he had pneumonia or bronchitis.

Lin was able to get through his first class with hardly a cough, gladly talking to the many students who came up to greet and thank him afterward. He offered a few first-class reflections: He felt comfortable talking about his own symptoms as if they belonged to a patient; he was unexpectedly emotional while introducing the class; and, while the letter from the terminally ill patient always stirs his heart, it was particularly resonant in the context of how this new class fits into his journey.

After all, how many patients with an incurable disease -- who, as Lin said "now have to think in terms of years rather than decades" -- get the chance to read their own letter of appreciation out loud? And before a packed house of mutually appreciative guests?

"This is more emotional than I expected," Lin said. "I am truly grateful and overwhelmed that so many students were interested in taking my class."

Check out the new

Health Compass podcast

Breaking down complex science and highlighting the innovators inspiring you to make informed choices for a healthier life.

WATCH IT HERE