Two decades ago, when my healthy, bright, energetic toddler, Leo, started having seizures, his neurologist sent us home with a list of five or six possible diagnoses. All were daunting and scary, but one, Dravet syndrome, stopped me in my tracks.

Dravet is degenerative and brutal. Seizures typically start before age 2, after which they intensify and diversify in type. Cognitive and social development often slow, stall and regress; so do strength and coordination. Early death is common.

Fortunately, Leo did not have Dravet but a more tractable form of epilepsy, which his doctors were eventually able to control. But between 10 and 20 children in the U.S. are diagnosed with Dravet each day; for these children and their families, any medical breakthrough brings long-awaited hope.

"There is no cure for Dravet, and we don't know how to control the seizures or adverse effects on brain development very well," said epilepsy researcher David Prince, MD, the Edward F. and Irene Thiele Pimley Professor of Neurology and the Neurological Sciences.

But research by Prince, postdoc Feng Gu, PhD, and Alzheimer's specialist Frank Longo, MD, PhD, the George E. and Lucy Becker Professor and chair of neurology, points to a new possible approach to treating Dravet. It's a small molecule -- LM22A-4, LM for short -- that unlocks a natural repair mechanism in a type of brain cell known as parvalbumin interneurons, which malfunctions in Dravet. The research was published Feb. 15 in PNAS.

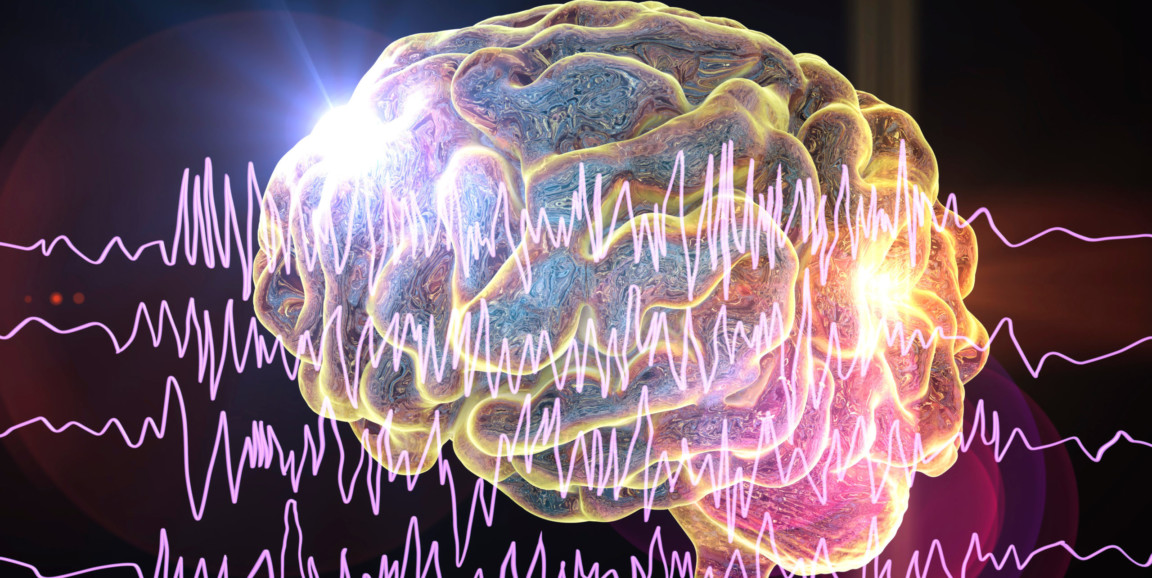

All brain function is roughly based on a sort of balancing act between excitatory neurons, which fire in response to stimulus or during cell-to-cell communication, and inhibitory neurons, which keep the excitatory neurons in check, ensuring that they don't fire too much. The parvalbumin brain cells are essential to maintaining the inhibition side of the brain's activity.

"Picture a balancing scale with excitation placed on one side and inhibition on the other," said Prince, who has been studying epilepsy for decades. "You get epilepsy if the excitatory side is markedly increased, or the inhibitory side is decreased, and the scale tips too far."

Overexcitement in Dravet

The seizures brought on by excitatory-inhibitory imbalance are like electrical storms in which millions of neurons fire out of control in ways that overwhelm the normally subtle orchestra of brain activity responsible for everything from movement to thought. Depending on where in the brain those electrical storms occur, seizures can cause anything from very specific movements or sensations, to the temporary alteration or loss of consciousness, to full-body convulsions.

The inhibitory parvalbumin interneurons disabled in Dravet are just some of the many neuronal players engaged in keeping brain cells from overexcitation, but their malfunction can increase the likelihood of seizures, resulting in a chronic and potentially lethal problem. By repairing those cells, and adding to the inhibition side of the scale, the brain's healthy balance can be restored, reducing the likelihood of seizures.

Scientists don't have an effective treatment for Dravet, but they do know how it originates: a genetic defect that damages the function of sodium channels in the parvalbumin interneurons. Activation of sodium channels allows a nerve cell to deliver signaling molecules to other cells and can have excitatory or inhibitory effects critical to maintaining a brain cell's basic operations.

Decreased function of sodium channels (occurring mostly in inhibitory neurons in Dravet) causes a decreased release of GABA, the main inhibitory signaling molecule in the brain. This tips the neuronal scale to the side of unbalanced excitation and seizures.

Longo and Prince's study showed that the small molecule LM helped restore the sodium channel function in inhibitory PV cells and reduced seizures and early death in mice with Dravet-like symptoms. The small molecule's power comes from its ability to mimic a protein called a neurotrophin, which increases the function of inhibitory neurons in the developing and mature brain.

When a particular neurotrophin, called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, is in short supply, as in patients with Dravet, the sodium channels in the interneurons malfunction. The neurotrophic factor also catalyzes the growth of new synaptic connections between neurons, a process key for the cell-to-cell communication that underlies learning and memory, two subjects of keen interest to both Longo and Prince.

The study showed that the therapeutic molecule was able to mimic the missing neurotrophic factor, activating the same receptors toggled by the naturally occurring neurotrophin, thereby repairing the sodium channels and making the brain less likely to seize.

In addition to quelling seizures in mice with Dravet-like symptoms, the study showed that treating rodents with the molecule also reduces the likelihood of premature death. Whether that effect results from the reduction of seizures or something else is still unclear.

Reducing seizures alone may be enough to explain the reduced mortality, said Prince. However, the cellular repairs caused by the small molecule may have other upstream neurological benefits that help correct unknown problems that may contribute to early mortality, he said.

"It's possible that the process brought on by the treatment could have multiple beneficial effects occurring in parallel," agreed Longo. "Very possible."

Beyond Dravet

Longo invented the therapeutic molecule a decade ago when he was at the University of North Carolina. After identifying the structure of active natural neurotrophins, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, he and his UCSF colleague Stephen Massa, MD, PhD, searched a computer database of millions of molecules, looking for any with similar structures that also fit the bill for a possible medication. (A therapeutic molecule cannot be too big, for example, otherwise it can't fit through the blood brain barrier, the filtration system that keeps harmful exotic substances from entering the brain.) Of dozens of candidate molecules, LM emerged as Longo's and Massa's favorite.

But it wasn't until years later, when Longo was talking with Prince, that they realized the small molecule might help address the cellular dysfunction underlying Dravet and other seizure disorders. In 2018, Prince's group showed that a similar trophic molecule prevented seizure activity in a rodent model of posttraumatic epilepsy.

A study by Longo published in 2020 showed that the molecule also effectively reduced symptoms in mouse models of Rett syndrome, another devastating childhood neurologic disorder associated with seizures and cognitive decline. Previous studies conducted in Longo's Stanford laboratory have likewise shown that the molecule improves the symptoms of mice with the rodent equivalent of Huntington's disease, a degenerative neurological disease that causes movement disorders and cognitive impairment.

The researchers also see an interesting connection between Dravet and Alzheimer's: The loss of synaptic connections between brain cells and the inability to build new connections could explain why children with Dravet so often slip into cognitive decline. Such loss may also be related to the cognitive damage that helps define Alzheimer's.

In another study by Longo's research team at Stanford, mouse models of late-stage Alzheimer's disease saw improved survival from the cellular repairs brought on by a slightly modified version of Longo's therapeutic molecule, he said.

"These are the kinds of things that can happen when you get an Alzheimer's person together with an epilepsy person," said Longo.

A medication based on LM that could help humans with Dravet with seizure control and the syndrome's other devastating symptoms may still be years off said the researchers. "But the point is," said Prince, "none of this was going on even five years ago."

Photo Kateryna_Kon