Lately, taking out the trash has been kind of difficult at my house. Seemingly never-ending snowfall this winter (I live in Montana) has left some daunting drifts that require boots and a coat to navigate. And now that things are just beginning to melt, there's a mess of mud. Frankly, often it's easier to just stash the bags right outside the back door, let them accumulate and take them several at a time to the trash can. But it doesn't make for a pretty sight.

Trash management is an equally important task in many cells, which have to carefully regulate their protein production and disposal in ways that maximize efficiency while minimizing clutter. To do so, they use storage compartments called lysosomes and a complex called a proteasome to deal with their cellular waste (much like how I utilize our back porch). It's a critical job; the accumulation of large protein clumps, or aggregates, have been associated with the development of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's.

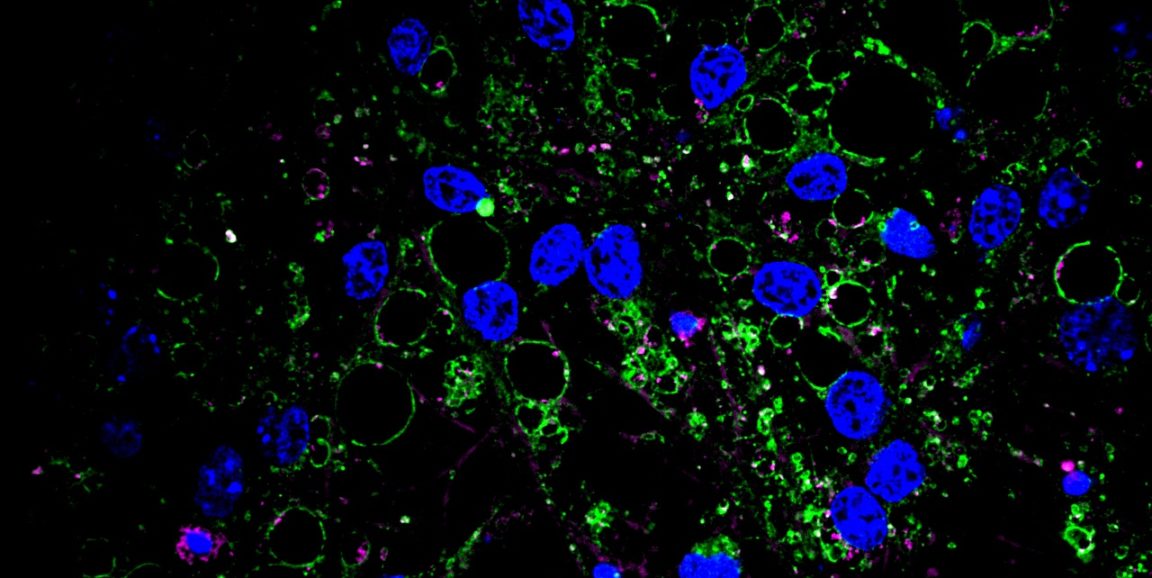

Recently, geneticist Anne Brunet, PhD, neurologist Thomas Rando, MD, PhD, and former postdoctoral scholar Dena Leeman, PhD, found protein aggregates such as these in a seemingly unlikely place -- young, resting neural stem cells in the brains of mice. They published their results today in Science.

As Brunet said in our release:

We were surprised by this finding because resting, or quiescent, neural stem cells have been thought to be a really pristine cell type just waiting for activation. But now we've learned they have more protein aggregates than activated stem cells, and that these aggregates continue to accumulate as the cells age.

The researchers had been looking for ways in which the gene expression profiles of resting and activated stem cells might differ from one another, and how aging affects the cells. (Rando directs Stanford's Paul F. Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging; Brunet is an associate director of the center.) When they compared the profiles, they found significant differences in the expression levels of lysosome-associated genes among the cells. Upon closer inspection, they found that the young, resting cells had lots of lysosomes, and those lysosomes were packed with large protein aggregates.

As Brunet said:

We were really struck by the differences between resting and activated stem cells in the expression of genes involved in protein quality control. The fact that these young, pristine resting stem cells accumulate protein aggregates makes us wonder whether they actually serve an important function, perhaps by serving as a source of nutrients or energy upon degradation.

Although the aggregates didn't appear to bother the young cells, the cells become less able to handle the aggregates as they age and their ability to respond quickly and appropriately to "make new neuron" signals was significantly hampered. Helping the cells clear the aggregates, or preventing their accumulation, restored the ability of the cells to respond like their younger counterparts, the researchers found. But mysteries still remain.

As Brunet said:

We'd like to know whether the aggregated proteins are the same in the young and old cells. What do they do? Are they good or bad? Are they storing factors important for activation? If so, can we help elderly resting stem cells activate more quickly by harnessing these factors?

Photo courtesy of Xiaoai Zhao