As a third-year medical student, Luisa Valenzuela, MD, was eager to begin participating in hospital rounds. But, one of her early case presentations didn't go at all as she had hoped.

Assigned to tell the medical team about a hospitalized patient, Valenzuela read the scientific literature on the patient's condition, took vitals and made notes from the person's chart, and paid close attention to how other case presentations were structured. When it was her turn to speak, she hoped the attending physician might compliment her clinical knowledge or her professionalism.

Instead, the attending said, "Wow, Luisa, you speak really good English."

"There was nothing about the papers I read, the physical findings, the work I did," said Valenzuela, now a resident in pediatrics at Packard Children's, at a recent Diversity and Inclusion Forum held Friday at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford.

In the context of rounds -- where everyone's English skills would typically be unquestioned -- the attending physician's comment was a classic example of microaggression, in which people say hostile or negative things based on implicit bias, unconsciously assigning specific traits to certain groups. If these subtle hostilities come your way only occasionally, you may be able to ignore their effects, as though they were stray mosquito bites. But the cumulative effect of many such "mosquito bites" is damaging.

Friday's session -- part of a half day of talks and workshops to promote diversity -- was planned to help Stanford's pediatric medical community understand how microaggressions affect the learning environment and patient care, and what to do about it.

To help the audience grasp the impact of being on the receiving end of microaggression, Valenzuela described her thoughts in the aftermath of the attending physician's comment about her English: Whaaaat just happened there? Am I being too sensitive? If I mention how awful it felt to receive this comment instead of having my work evaluated, will the attending think I'm attacking her? On the other hand, if I don't say anything, will she do this again to another medical student?

And also, in spite of a strong academic track record, Valenzuela wondered: Do I fit? What if I don't? Maybe I don't belong here.

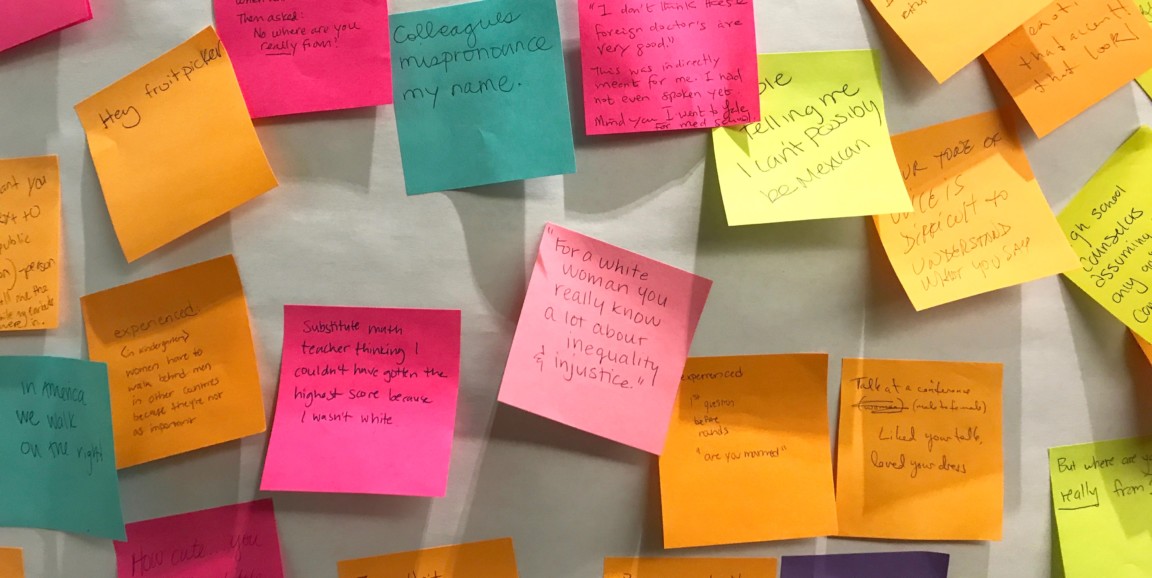

Audience members were then invited to describe microaggressions they had experienced, witnessed or committed on sticky notes, then read others' contributions. Attendees shared microaggressions including: "Substitute math teacher thinking I couldn't have gotten the highest score because I wasn't white," "Are you a patient? You're too young to be a doctor," and "But where are you really from?"

Examples of microaggressions committed included "Commending someone in a wheelchair for showing up to an event," "Automatically speaking to a Latino family in Spanish," and "Saying 'You don't look Hispanic.'"

The session also described strategies for addressing microaggressions productively. Michael Maurer, MD, a resident in pediatrics, led the audience through several tactics, including:

- Inquiring -- "What do you mean by that?"

- Making an impact statement -- "I was thinking about what you said, and it hurt me because the focus of your content had nothing to do with my presentation."

- Reframing -- "How would you feel if this happened to you?"

- Revisiting after the fact -- "Do you remember the conversation where you mentioned ...?"

Keeping the tone of such conversations non-blaming and open is important, Maurer said.

Presenters and audience members discussed challenges they face trying to respond to microaggressions. For instance, because medicine is so hierarchical, it can be intimidating for trainees to address their superiors, and trainees may be reluctant to speak up as they become more invested in empathizing with the group of senior physicians to whom they want to belong, attendees noted. Observers can help by commenting on microaggressions so the pressure on those who receive them is reduced, session leaders said. Educating hospital and medical school leaders is beneficial, too.

"Microaggressions won't be eliminated, but we can focus on creating a safe working environment where they can be discussed," said pediatric resident Alyssa Honda, MD, who co-led the session.

Other topics addressed at the forum included handling discrimination directed at medical staff by patients and their families, understanding bias and providing better care for patients and families with limited English proficiency. Organizers at the Office of Pediatric Education said they plan to make the Diversity and Inclusion Forum an annual event.

Photo by Erin Digitale