Anyone who spends time outdoors probably stops to listen when an animal attack is severe enough to make news. They might even take extra precautions when venturing into the wild. Think tying bells onto hiking boots or carrying bear spray in Yellowstone.

But a new study shows that the best way to avoid being injured by an animal might be to focus a little closer to home, and on much smaller animals — insects, dogs, rats or snakes.

In fact, non-venomous animals like mosquitos are considered the largest threat for injury, something Joe Forrester, MD, a Stanford surgeon in trauma and critical care, said is simply a matter of numbers — they make up the greatest percentage of animal life in our environment.

And that will only grow, said Forrester, who suggested that, along with having an ongoing national conversations about gun violence and other forms of death, consideration should also be given to the impact of injuries from animals.

"The reality is we still interact closely with the natural world," said Forrester, lead author of a study published in Trauma, Surgery & Acute Care Open. "Our existence is interwoven with the world we live in. As development and climate changes affect us more, these interactions with animals are likely to be more common."

Over the five-year period from 2010 through 2014, there were nearly 6.46 million animal-related injuries treated in emergency rooms across the United States, at a total cost of about of almost $5.96 billion, according to the study.

Forty-one percent of those injuries were caused by non-venomous animals called arthropods, such as mosquitos, ticks and spiders. Forrester said that besides suffering bite injuries, people also were treated for vector-borne conditions, such as West Nile virus, malaria and Lyme disease.

Dog bites accounted for 26 percent of the injuries and hornet, wasp or bee stings accounted for 13 percent.

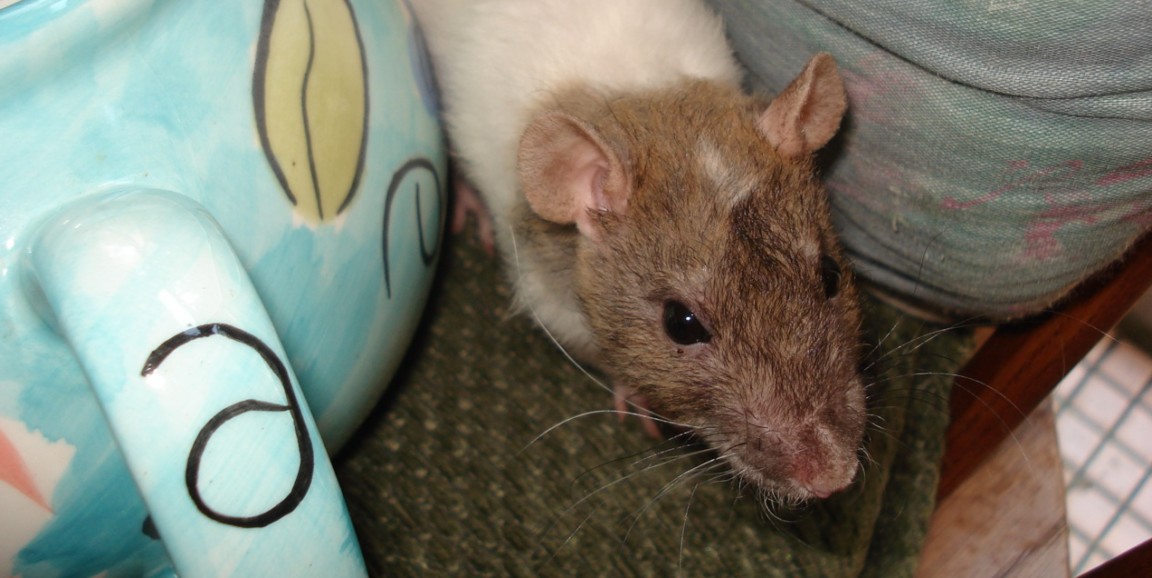

Though only 1,162 (or .02 percent) patients died as a result of animal-related injuries, bites by non-venomous arthropods caused the most deaths during the study period at 278. But when considering death rates per 10,000 people during that period, rats were the most deadly: 6.5 per 10,000 people died after rat bites; 6.4 after venomous snake or lizard bites; and 6.1 after dog bites.

The study, Forrester said, was designed to examine the "considerable financial burden in the U.S. due to animal injuries." Past estimates were based on data from county-level death certificates. Forrester and his colleagues used data submitted to the National Emergency Department Sample, which provided a broader and more complete analysis than previous studies.

Other researchers on the study were Jared Forrester, MD, a general surgery resident; researcher Lakshika Tennakoon; and senior author Kristan Staudenmayer, MD, associate professor of general surgery.

Joe Forrester noted that the estimated annual health care cost of $1.2 billion doesn't include physician fees, outpatient clinic costs or such follow-up care as rehabilitation. It also doesn't account for lost wages. In all, he estimates that the overall financial impact on the country is closer to $13 billion a year.

Being aware of the data could lead to better intervention, Forrester said. For example, the people who are most vulnerable to dog attacks are also the least likely to be able to defend themselves — the very young and the very old, he pointed out.

"The opportunity for preventing dog bite injuries is making sure parents of young children and people who care for the elderly know the risks associated with a dog in the home, and how to prevent them," he said.

Photo by supernova