Stanford infectious disease expert Desiree LaBeaud, MD, spends much of her time trying to understand interactions between humans and mosquitoes.

"People don’t recognize that there are lots of different mosquito species and all the different mosquitoes have their own little mosquito behaviors," LaBeaud told me recently. I was interviewing her for a feature story in Stanford Medicine magazine about her team's work to map outbreaks of Zika, dengue and chikungunya, three viral illnesses spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

The diseases are on the move throughout Africa and Central and South America, where LaBeaud's team does most of their research. But these viruses also have the potential to become established in mosquitoes that live in the United States.

Understanding the behavior of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes is important for predicting and preventing outbreaks of viral illnesses, LaBeaud's team has found. For instance, unlike the mosquitoes that transmit malaria, Aedes mosquitoes like to breed in man-made containers. That presents a challenge for mosquito control in developing countries, where households often store water in large containers to protect against unreliable supplies from local taps or wells.

To learn more, LaBeaud's team conducted a house-to-house survey of mosquito breeding sites in a coastal region of Kenya. Jenna Forsyth, a graduate student who helped run the project, explained what happened:

'We went in thinking, 'It’s going to be the prominent containers we know about, the big jerrycans that are 10 or 20 liters,'' Forsyth said. Instead, they discovered that 80 percent of mosquito breeding was happening in 'containers of no purpose,' many of which were trash. Other such containers were being kept in a family’s yard 'just in case they were needed.'

'It turns out that a lot of the containers used for drinking and cooking don’t sit around long enough for mosquitoes to breed,' said Forsyth. When designing the next steps of the project, they realized they had to target those irregularly used containers. 'It’s meaningless if we just say, 'Dump out your buckets.''

Instead, the researchers went on to challenge 250 schoolchildren to collect "no purpose" containers, and the kids brought back more than 17,000 of them, or 1,000 kilograms of plastic waste. The team is working with local collaborators in Kenya to set up a sustainable program to collect such trash on an ongoing basis, and to educate people in the communities where they work about other ways they can help control mosquitoes.

Since there are currently no drugs that target dengue, chikungunya and Zika, changing human-mosquito interactions is likely to be the best way to stop these diseases for some time to come, LaBeaud told me. And that's true not just in the developing world, but also here, where Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are already living:

'Humans can get anywhere in the world in 24 hours, and so can these infections,' LaBeaud said. 'They come in us. We go on vacation, the virus gets in our blood, we come home and, if the vectors are there, it’s a perfect storm waiting to happen.'

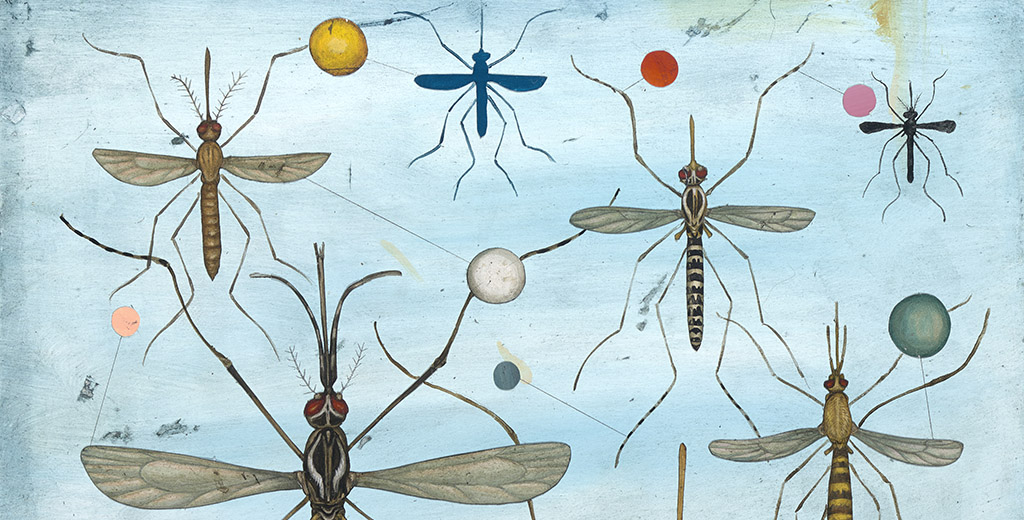

Illustration by Jason Holley