When Barbie Barrett, MD, was in Haiti providing medical care following the 2010 earthquake, she was approached by a barefoot man with one leg who asked for her shoe.

"What could I say? I gave it to him," Barrett, a clinical associate professor of emergency medicine, recalled to me recently. "The next day he came back with a friend who was missing the other leg, so of course he got my other shoe. A woman came in with breast metastasis requiring tight bandaging, so I gave her my bra to bind the bandages. By the time I got on the plane to come home, I'd recycled my remaining outfit and underwear so many times that I stunk. On the plane there was an emergency and they asked if there was a doctor on board. You can only imagine what they thought when I popped up!"

Barrett is no stranger to either handling disasters or defying expectations. After graduating from Western Michigan University, she had her sights set on becoming a doctor, but her father, a general surgeon, told her to first go to Vietnam in 1971 for an American Red Cross Tour of Duty.

"He said, 'If you can handle war, you can handle being a doctor.'" Barrett went to Vietnam, but when she returned to the states and was accepted to medical school, her father wasn't happy. "You would have thought a funeral had taken place in our house," she remembers. "He thought I had taken the space at medical school of a young man."

The 1970's weren't welcoming to female physicians, and while her father eventually came around, Barrett was marginalized in the hospital. "I was never 'doctor.' I was 'sweetheart' or 'honey.' We couldn't use the doctors' lounge." She qualifies though, "For everyone who acted like a jerk, there were good people. It was character building. And because I was one of the few females in the specialty, I had other opportunities."

That list of opportunities is very, very long; her CV runs to more than 20 pages and includes serving as first responder to such tragic events as the 1978 Continental Airlines crash at LAX, the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, the 1996 Atlanta Olympics bombing, the 2013 Philippines typhoon and the 2018 California Camp Fire.

When Barrett travels to disaster areas she not only brings expendable clothing and medical supplies, the mom of six also brings glitter, a be-dazzled stethoscope and Barbie bandages in her sequined "ready pack." There are always little kids at a disaster site, she points out, plus "your biggest job in a disaster is to make people smile."

Barbie Barrett as Miss Teen World in 1967

Barrett in Vietnam on an American Red Cross Tour of Duty between 1969-1970

Barrett got around via water buffalo in the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan washed the roads away in 2013.

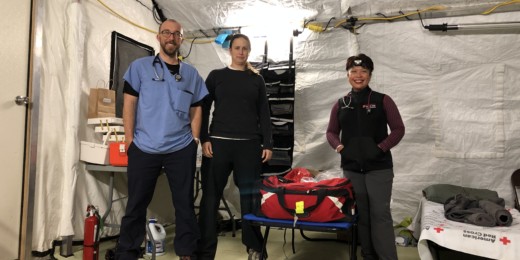

Barrett at a makeshift clinic in an elementary school in the Philippines in 2013.

Barrett providing emergency medicine services in Papua New Guinea in an undated photo.

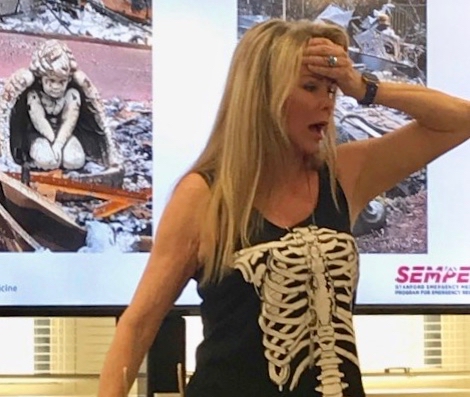

Barrett talks to Stanford Med School 101 participants in 2019 about disaster aid preparedness. She's showing what she wore at one location under her scrubs, which she ripped up to use for bandages.

Unfortunately, in disasters there are also difficulties and risks, including looters and violence. Barrett recalls her time at Port Au Prince General Hospital in Haiti, when armed guards protected the physicians as they walked through streets covered with bodies on the way to a classroom-turned clinic where patients lay on the floor. ("We had one sheet for all of them," she recalls. "One sheet that people bled on, died on, gave birth on... then at the end of the day you take it home and try to wash it in cold water because that was all you had.")

One afternoon, the group was told to drop to the floor in case looters outside started firing. The nurse lying beside her offered Barrett a knife for protection. Scenarios like that inspired Barrett to become certified in ballistics and firearms training and complete Hostile Environment Awareness Training.

Yet when I ask about the worst aspect of life in the disaster zones, she says, "The lack of discrimination. Older people should be taken, younger should be left, but a disaster doesn't discriminate. I've had to bury babies. It's one thing to carry a coffin, another to carry a small box."

When she's not out of the country or in the Stanford Emergency Department, Barrett runs a private practice in anti-aging medicine, and she has just completed a book on hormones. The effort balances her disaster work: "I want to provide proactive as well as of reactive medicine."

Does this mean that's she's done with disaster medicine? Never, she says. As a a member of Stanford Emergency Medicine Program for Emergency Response, Barrett is in a sense always on call. And she prefers it that way.

Photos courtesy of Barbie Barrett, Susan Coppa and Patricia Hannon