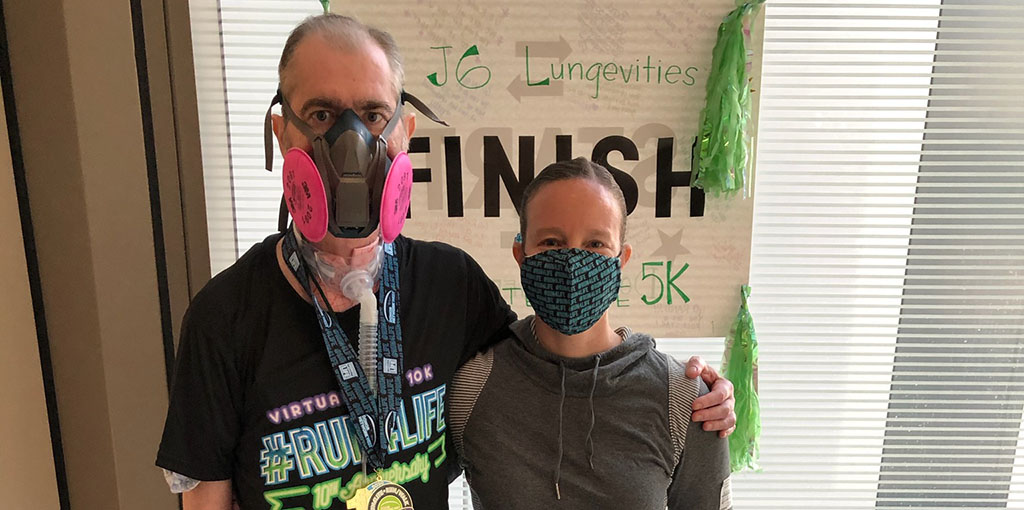

On a Saturday last September, hundreds of walkers and runners hit the trails and the treadmills, putting in miles to raise money for organ donations in California. But Rand Bresee, 46, took to the halls of Stanford Hospital instead.

Bresee received a new heart and lungs in February 2020. When a few transplant nurses, including Liz Orgon, MSN, were organizing a team for the walk, Bresee -- the unit's frequent walker who was also lifting weights and cycling with small foot-powered pedals -- was a natural fit. Orgon asked if he wanted to join the team. "You could see his eyes light up," she said. Bresee was in.

On the big day, Sept. 12, Bresee was joined by his wife, Michelle Bresee, who relocated from Oregon -- where the couple live with their two daughters -- to the Bay Area to stay near him during his hospitalization.

In bright red sneakers and a black #Run4Life T-shirt, Rand Bresee prepared to walk a 5K, the equivalent of about 40 laps around the unit. A nurse or aide was prepared to wheel his oxygen behind him.

Before his health declined in the late 2000s, Bresee did yoga, lifted weights and walked several miles regularly. But post-surgery, a 5K was a lot for him. His plan was to start slow, breaking the walk into four parts. The first session went well. "On the second and third walks, I was building up steam," Bresee said.

"Afterward, he said he felt like he could have gone farther," his wife said.

The key, Bresee said, was developing a rhythm -- timing his steps to his breathing, using a count of four: sharp inhale on one; exhale two, three, four. It was a practice he had to hone while training his lungs how to breathe again. He often felt like he was breathing through a straw.

"The counting helps you breathe and suck through that straw," he said. "And the more you do it, the bigger that straw gets."

Heading for a transplant

Bresee was born with transposition, a condition of the great arteries whereby the positions of the pulmonary artery and the aorta, which carry blood out of the heart, are switched, causing the body to get too little oxygen. He required several heart surgeries as a child and spent a year of his youth in the hospital.

As he went to college, met Michelle, pursued his career and started a family, he had periods of good health. But in 2008, he was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, marked by high pressure in the vessels that carry blood to the lungs.

For a decade or so, Bresee moderated his decline with medication and exercise. But the condition of his heart and lungs continued to worsen and, by fall of 2019, he became eligible for a heart and lung transplant.

The Stanford Medicine heart-lung transplant program is one of the biggest in the country, one of the few capable of handling Bresee's complicated condition, and the closest to the Bresee's home. It was a straightforward choice.

Bresee was ready to head to California the minute Stanford called, having already packed a bag for the hospital stay. The call came on Feb. 24, 2020, and the couple hustled to Stanford. The surgery began the next morning.

The drive to recover

The organs gave Bresee new life, but he had an arduous road ahead. He threw himself into his recovery, even during the lonely months when Michelle Bresee was not able to visit the hospital because of the pandemic.

"I'm a very driven person. I'm also passionate about getting through it," he said. "I have a very strong will to live."

As complications arose, his Stanford Medicine care team carefully navigated them, drawing on the institution's depth and experience with complex cases.

"We have this incredible multidisciplinary team that gave him this opportunity," said Joshua Mooney, MD, clinical assistant professor of medicine, who helped treat Bresee. "And Rand has done everything and more that we've asked him to do. He and his wife are very motivated. A lot of credit needs to go to them."

Happy to be together

Bresee participated in the Donate Life Run/Walk to raise awareness about the need for organ donation, but also to debunk stereotypes about transplant patients. "It's not just someone who smoked or drank too much," Bresee said. "It can be just a regular person who looks and acts like everyone else. It's important not to judge."

Two months after the walk, Bresee was ready to leave the hospital for the first time since his transplant. Nurses and doctors lined the hospital's halls and bid him farewell as music played.

After arriving at a nearby apartment his family rented to continue his ongoing care, Bresee enjoyed a steak and potato dinner, and was grateful to be able to spend time with his daughters, Blakely, 15, and Gretchen, 12.

Now, they are back home in Oregon and settled into a routine: Michelle Bresee works remotely and the girls attend school online as Bresee continues to focus on his recovery.

"It's just nice being together," Michelle Bresee said. Eating oatmeal together, talking or not talking, just living a quiet life, has taken on a new importance. "Even when he's not feeling good, we're still just happy to be together."

Thinking back on the months-long hospitalization, the Donate Life walk stood out, the Bresees said.

"When we think of the top five moments, for me, it was the top moment," Michelle Bresee said. "It felt like we were actually getting to experience life, not just being sick or trying to heal."

Images, including top photo of Rand and Michelle Bresee, at the end of the Donate Life walk at Stanford Hospital, courtesy of the Bresee family.