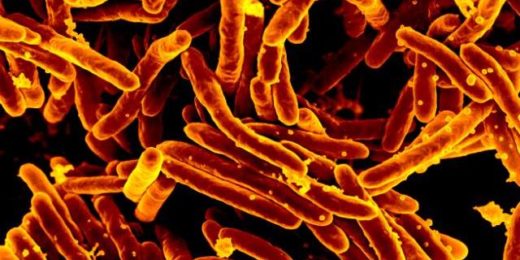

At more than 10 million cases per year, and 1.5 million deaths, tuberculosis is as pervasive as it is deadly. But modern medicine has dramatically cut fatalities, thanks to antibiotics that kill the bacteria responsible for the disease.

Still, the treatments aren't always a silver bullet, and it's widely known that even prescribing the most common drug used to treat and prevent TB, isoniazid, is, in some ways, a shot in the dark.

"It's well documented that people who take isoniazid have highly variable responses, even with standardized doses based on weight," said Jason Andrews, MD, associate professor of medicine. "It's been this way since the 1950s."

The hit-or-miss drug dose results aren't for a lack of understanding. Researchers know, for example, that some people's bodies are genetically wired to gobble up the drug and metabolize it quickly, while others' bodies turn drug metabolism into a lengthy affair. Either way, patients don't get enough of the drug or they get too much, which causes toxicity. Only about half of the population processes the drug "normally."

Now, Andrews and a team of scientists have devised a way to quickly and reliably test a person's genetic predisposition for metabolizing the drug so the proper dose can be prescribed. The team recently published a paper detailing the results in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Too hot, too cold, just right

An enzyme in the body called NAT2 is responsible for driving the metabolism of isoniazid. Past genetic analyses have shown that mutations in the gene encoding that enzyme are common across different populations, causing varying levels of isoniazid metabolism.

In East Asia, about 40% of the population metabolizes the drug too quickly, putting many at risk of receiving a dose that's ineffective at preventing or treating infection, Andrews said. But in Europe, Africa and the Americas, the prevalence of slow metabolizers is much higher, increasing the chances that they will experience liver toxicity fourfold.

"Despite the fact that this variability is well established, nothing has changed in 50 years," Andrews said. "If you're receiving a dose in Palo Alto, or if you're receiving it in Cape Town, you get the same standard weight-based dose of the drug. For half the population, it's the wrong dose."

What was needed was a quick, easy test that could tell doctors if their patients were normal, slow or fast metabolizers or, as Andrews puts it, "too hot, too cold, or just right." So he and his team created a rapid molecular test that spits out readouts of how an individual will metabolize isoniazid.

"There's never really been a way to test for this quickly and get an answer that helps you give the right dose," said Andrews. "So that's where our innovation comes in."

Developing the test

To create the test, Andrews and his team started by gathering public genomic data from 8,500 people around the world who had been treated with isoniazid. By scouring the data for where certain mutations in the genome occurred and how each patient faired under isoniazid treatment, the team trained an algorithm to predict which mutations impacted isoniazid metabolism. In the end, the algorithm could predict normal, fast or slow metabolizers of the drug with over 99% accuracy.

"We developed this test on a rapid molecular platform, which is endorsed by the WHO for tuberculosis diagnosis, and is widely used in low and middle-income countries," said Renu Verma, PhD, postdoctoral scholar. "Our test provides results in 140 minutes and can be performed with a drop of blood with minimal hands-on time and training. This makes precision medicine more accessible to resource-constrained settings where the majority of the TB burden falls."

To verify their findings, the team collaborated with researchers in Brazil to test their algorithm on a cohort of 48 patients who had been diagnosed with TB. The patients were treated with the standard dose of isoniazid and researchers tracked levels of the drug in the patients' blood over the course of two weeks. Researchers then compared how quickly the patients cleared the drugs from their systems with how the algorithm had predicted their bodies would metabolize the drug.

"This was kind of a proof of concept to see if we could predict patient drug clearance just by looking at information from their genome," said Andrews. "We were able to do so highly accurately."

The team plans to conduct clinical trials on the method next. Andrews said that, if all goes according to plan, their approach could not only be used to guide dosing of isoniazid but also to other key drugs used for tuberculosis treatment.

"The advent of tuberculosis therapy has been one of the most impactful medical advances in the past century, but we know we can do better for patients than one-size-fits-all treatment," said Andrews. "Our goal is to utilize genomic data to develop precision medical tools that improve care for this pervasive disease."

Photo by greenapple78