Desiree LaBeaud, MD, and Jean Shin work in very different professions, but they are united by a single passion: plastic.

LaBeaud, a professor of pediatrics at Stanford Medicine, and Shin, a distinguished New York artist, have joined to create two monumental sculptures of discarded plastic waste that they hope will persuade people to rethink how they use the planet-choking material.

"Only 9% of the world's plastic is recycled. Most of it is poisoning the land in poor countries, where it is sent," LaBeaud said. "Here we are making something beautiful out of it and, we hope, inspiring people to take individual and collective action to decrease their use of plastics."

LaBeaud researches mosquito-borne diseases in the developing world and has recently discovered that plastic waste is a breeding site for disease-causing mosquitoes. Shin collects discarded objects and transforms them into installations to spark conversations about the cumulative effect of consumer materials on the environment.

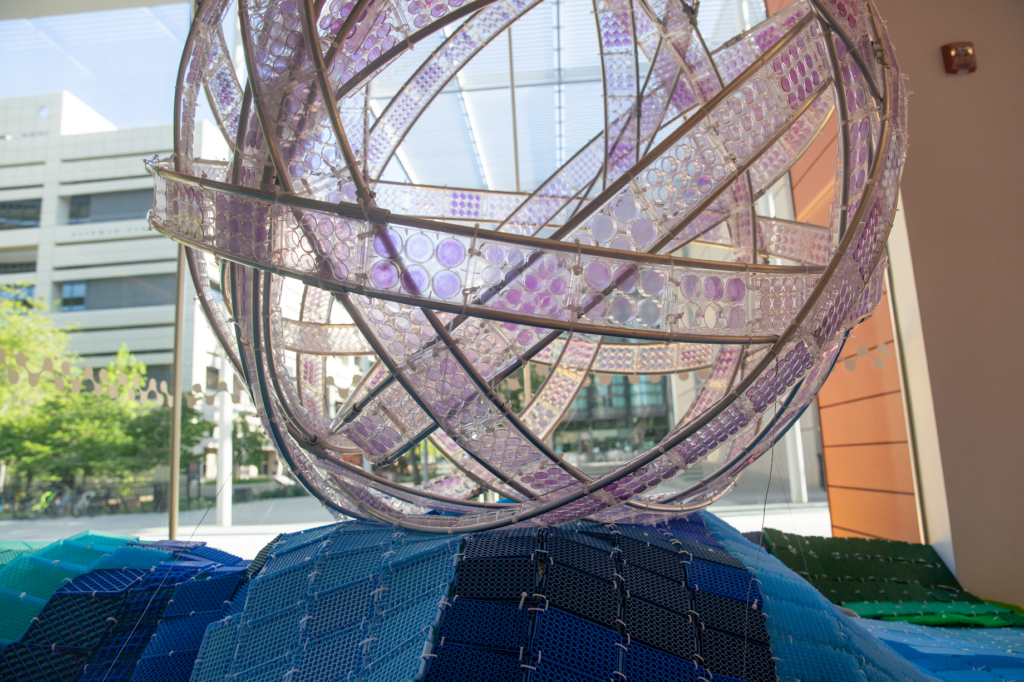

On May 16, before a crowd of some 50 people, the two unveiled one of their collaborative artworks, Plastic Planet, a lavender sphere built from plastic waste from medical school and campus labs.

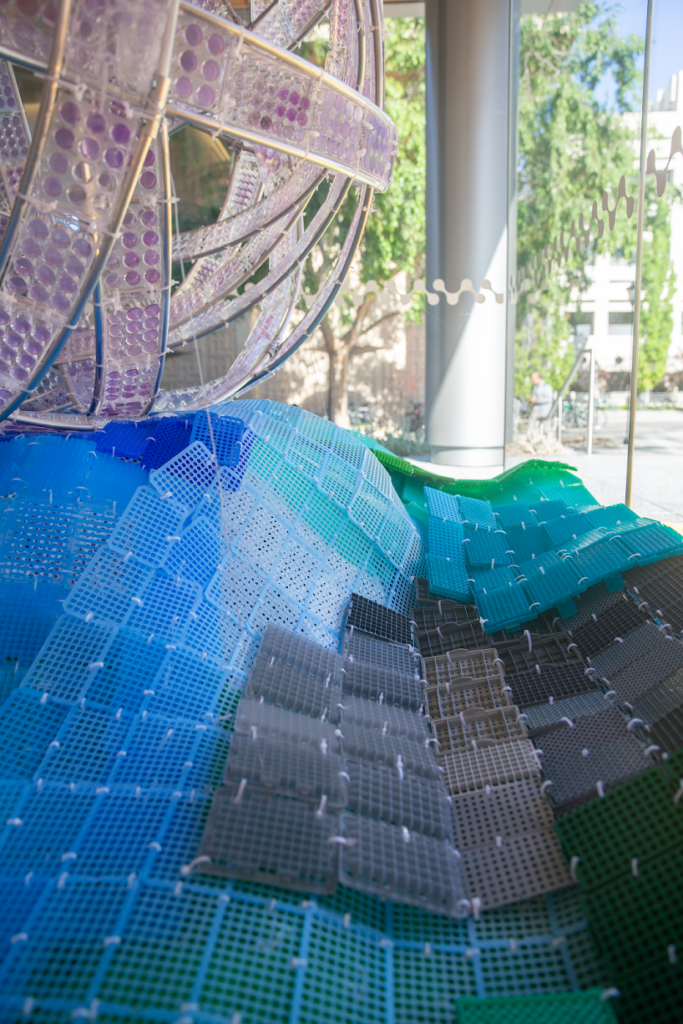

The sculpture, which stands in the lobby of the Biomedical Innovations Building at the Stanford School of Medicine, resembles a planet, a molecule or an atom, depending on the viewer's perspective, Shin said. It is made from viral plaque assays from the LaBeaud Lab and other campus virology labs and stands on a 7-by-10-foot base of blue, green and violet plastic medical waste, mostly discarded pipette tip boxes.

A threat to human health

"For me, it highlights a paradox," Shin said of the sculpture. "The scientific community is driven to find solutions for our health, but in doing their work, the medical research labs and hospitals are increasingly dependent on single-use plastic which is harming the planet. This needs to change."

LaBeaud said that much of the sculpture's material was taken from her lab when she was researching arbovirology -- viruses carried by vectors such as mosquitoes, ticks and sand flies. "We are trying to heal the world and protect ourselves from these viruses, yet the way we do that is threatening our health and the health of our planet," said LaBeaud, whose work in Kenya is featured in the newest issue of Stanford Medicine magazine in an article about a number of Stanford Medicine projects aimed at countering the negative effects of climate change.

She noted that plastic containers can trap water and become a haven for mosquitoes, which can spread diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever.

LaBeaud and Shin received an $80,000 grant from the Denning Visiting Artist Fund to support their project here at Stanford University and in Kenya. At Stanford University, it involved as many as 100 people from across the university -- students, staff and faculty at the Stanford University design school; the Stanford School of Medicine; the School of Humanities and Sciences, and other schools. They attended workshops on how to assemble plastic units that would later become part of the larger sculpture.

Bethel Bayrau, a life sciences research professional in the LaBeaud Lab, helped retrieve thousands of pieces of plastic debris from various labs for the structure.

"It was a unique experience," Bayrau said, noting that working with these materials was different from working with them in the lab, which involves many constraints. "It was a reflective time for all of us to realize how much plastic waste we are creating;" she said.

The sculpture is a companion to a similar art piece in south coastal Kenya, where LaBeaud co-founded the nonprofit Health and Environmental Research Institute-Kenya to educate people about the environmental and health hazard of plastic, find solutions to the pollution crisis, and improve community health.

The group hired some 50 local residents to transform more than 7,000 single-use plastic water bottles into a massive blue ocean wave, called Sea Change, in the center of Diani-Ukunda in southern Kenya. The sculpture was unveiled on Earth Day in April.

"The beautiful, massive wave already has become a landmark. It has received a ton of media coverage and sparked thousands of discussions," said LaBeaud, a senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment. "We are using that sculpture to bring about a shift in cultural norms and promote sustainability as a collective value."

Her goal, she said, is to "start a revolution against single-use plastic. We need to have people feel inspired and say, 'I really care about this, so I'm going to make my actions align with my values, and I want my values to align with the planet.'"

Photos by Katie Han