Lisa Ward led off a May gathering at the White House for President Biden's Cancer Moonshot initiative by recounting one of her most stirring moments as a mother. Upon learning that his aggressive form of brain cancer had no known cures, Ward's teenage son looked her in the eyes and said: "Mom, I'm not afraid to die -- I'm afraid to not make an impact before I die."

It's been two years since Jace Ward died from a rare form of cancer known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma at age 21. The disease devastates families, typically stealing their loved one within a year of diagnosis.

But Ward defied those odds, living long enough to become a vocal advocate for young patients like himself and to illustrate the possibilities of a novel immunotherapy technique through his participation in a clinical trial led by Stanford Medicine pediatric neuro-oncologist Michelle Monje, MD, PhD.

The study of engineered immune cells known as CAR-T cells revealed a breakthrough in understanding brain cancer's biological underpinnings -- and Monje referred to Ward and the three others who participated as "heroes" in the war on cancer.

Now, at the behest of Biden, who lost his son Beau to brain cancer in 2015, it's up to the best and brightest in academic research, governmental regulation and patient advocacy to show Ward-like fearlessness in launching an interdisciplinary attack on the most lethal forms of a disease that kills more than 600,000 Americans annually.

"We've got to make strides for patient care in the short term and find cures in the long term," said Monje, professor of neurology. "Now is the time for team science and diversity of perspective."

Shooting for the moon

The goal of the Moonshot initiative -- named after President John F. Kennedy's audacious 1961 vow to put a human on the moon -- is to cut the death rate from cancer by at least 50% over the next 25 years. How? By bridging chasms between scientific research and therapeutic solutions, beginning with a focus on cancer's most deadly forms.

"We're not moving fast enough on these cancers where patients suffer terribly, and that's inexcusable," said Stanford Medicine's Paul Mischel, MD, professor of pathology and vice chair for research in the Department of Pathology, a member of the Stanford Cancer Institute and a scholar at Sarafan ChEM-H.

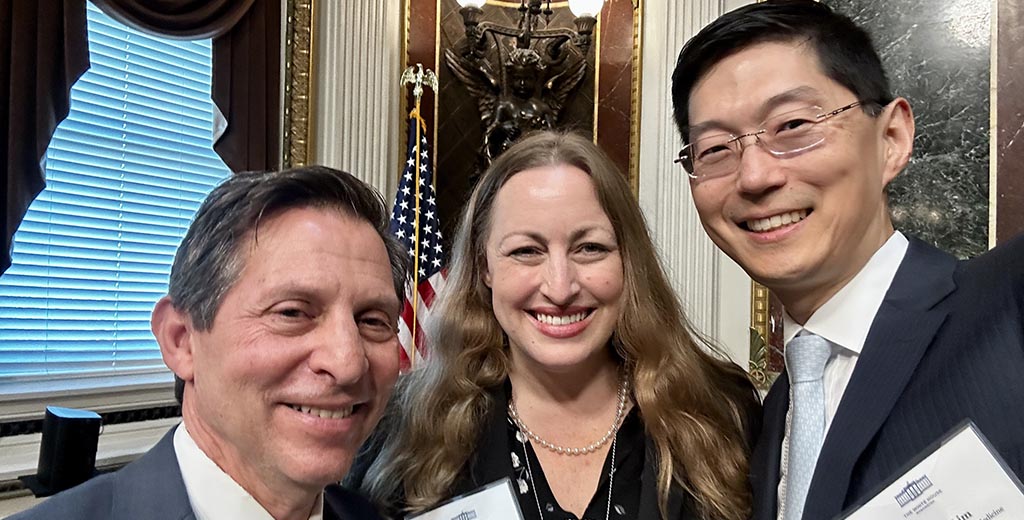

For the deadliest forms of brain cancer, it will be up to experts such as Moonshot invitees Mischel, Monje and their Stanford colleague Michael Lim, MD. They were joined in Washington, D.C., on May 25 by other thought leaders from across the advocacy, patient, research and health care communities for the Cancer Moonshot Brain Cancers Forum, focusing on glioblastoma multiforme and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. The first version, known as GBM, most often affects adults while the second, DIPG, is a pediatric brain cancer.

"These are really bad diseases, and truthfully there has been almost no progress in about 35 to 40 years," Mischel said.

Can engaging the foremost experts in team science change things? As Lim, professor and chair of neurosurgery, said, "If the COVID vaccine showed us anything, it's that we can do so much more if we start coordinating."

Stanford Medicine's contribution

Mischel said the commitments he saw at Stanford Medicine toward bridging gaps with creative, collaborative efforts -- the Innovative Medicines Accelerator or IMA, for instance -- convinced him to leave the University of California, San Diego two years ago.

"We're already doing it, and it speaks volumes about the scientific gravitas here," he said. "I had never seen anything like the IMA, which sits in that space between science and early-stage biotech. It is exactly that risk space that we need to jump into and fix."

Mischel -- who lost his father to cancer as a young boy -- is also involved in the broader fight, thanks to molecular-level discoveries. The Mischel Lab has pioneered research into extrachromosomal DNA, or ecDNA, which has been found to aid rapid and aggressive malignant transformation in many tumor types, including in malignant, aggressive brain tumors.

Monje's work revealed that these cancers integrate into neural circuits, and that CAR-T cells can disentangle this network of cancer cells in the brain, work that has brought renewed hope that life-saving therapies for gliomas can be found. The Monje Lab has discovered breakthroughs in the neuroscience of brain cancers, demonstrating that GBM and DPIG take advantage of nervous system activity to drive tumor initiation, growth, invasion and progression.

Lim has been recognized as one of the world's foremost experts on immunotherapy for brain tumors. The Lim Lab focuses on understanding basic mechanisms of immunosuppression in glioblastoma and identifying checkpoint inhibitors, which remove the brakes from immune cells and have been shown to improve survival in multiple cancer types.

After returning from D.C., the three specialists reflected on their hope for progress and Stanford Medicine's place in the conversation. The following Q&A is based on their observations.

Can you speak to the significance of the Cancer Moonshot initiative?

Lim: There's a sense of urgency. We've got to move faster for our patients. We've got to find a cure. And it's not only for the patient but also the families. Even after the patient passes away, the families are left with the remnants of that disease.

Mischel: There have been so many advances in so many types of cancer for patients, but there are others that are incredibly recalcitrant. That's what I spend my time thinking about.

The idea is to get people to work in a way that's different and to get different kinds of people together -- not only academics, but also people from biotech; from other branches of government; and, maybe most importantly, patients, advocates and their families. Those are the people you want to hear from with ideas on how we can break this logjam. Because the system is not working well for them.

Monje: We have found the kinds of therapeutic responses we might once have only dreamed of, yet we now need to make those responses available for every patient. On our CAR-T cell trial, I've seen kids get better, at least for a while, and in some cases for a long while.

CAR-T cell therapy holds so much promise. There are so many of us -- including Crystal Mackall and the Center for Cancer Cellular Therapy here at Stanford -- who are leveraging the really hard work done over the past 10 to 20 years have started to see some exceptional responders, telling us it's possible. But we have to figure out what is limiting the therapeutic response for other patients.

What are the biggest hurdles to collaboration and real progress?

Monje: We need to break down silos -- between institutions, between fields. Many of the truly transformative breakthroughs have come at the intersection of disciplines. We have to look at it from multiple perspectives -- not through the lens of just cancer biology, just immunology, just neuroscience -- and see every angle. Progress will likely require private-public partnerships between government and academia and industry.

Lim: There's a clear consensus that we don't understand the biology of this brain cancer and that we have a lot more to learn. Because it's a rare disease, we have to coordinate access to medical records and standardize specimen collection from brain tumor patients across the country to better understand the biology and natural history of this.

We'll need some bold initiatives from the National Institutes of Health, for example, to help fund the institutes that promote team science. I also think the government is starting to understand that there's a lot of paperwork that has to pass between two institutions to be able to get something to happen. We need to simplify that so we can start sharing data.

Mischel: Thirty-five years of failures have meant that this is a place where most biotech and early-stage ventures have not wanted to go. Most of the work has been on drugs that have worked in other parts of the body, not optimized right for the particular needs of those brain cancer patients.

Beginnings are always complex. Before something like Moonshot takes form, you first need a marketplace of ideas. The question will be how to shape this in such a way that it will most quickly make a difference for patients who need it most. It's got to be about science, but it also has to be about regulatory policy and insurance because these people need to be able to have access to the treatments. It needs to be about creating an environment where the science can go to biotech seamlessly.

Can you speak about Stanford Medicine's involvement in cancer research?

Mischel: The idea of the Moonshot is not that the government will fix this. Instead it's "Come together, share ideas and go fix it ourselves." And that's what we're doing here at Stanford. For instance, the IMA is unique. It's remarkable that the Cancer Grand Challenges Program on ecDNA is anchored here. It brings together the best people in the world, spanning very diverse disciplines -- chemistry, genetics, immunology, computational biology, evolutionary theory, mathematics. I think we're a model of a different kind of science.

And I tried very hard to suggest at Moonshot that we be thinking about these kinds of team efforts, where you're much more nimble and can aggregate into strike teams to handle very specific problems. We're driving that type of team science at Stanford, and positioned to go from science to medicine quickly, so we feel a sense of responsibility to push it forward.

Top photo of Stanford Medicine cancer physician-researchers Paul Mischel (from left), Michelle Monje and Paul Mischel at the Cancer Moonshot Brain Cancers Forum on glioblastoma multiforme and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma in Washington, D.C. on March 25, 2023 (Photo courtesy of Michelle Monje).