Lawrence Steinman thinks he may know more about baseball statistics than neurology -- and that's a feat, considering he's been a neurologist for over 43 years. As a baseball enthusiast, he vividly remembers listening from a record player as Lou Gehrig, a beloved New York Yankee player who had developed amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), delivered his emotional "Luckiest Man" speech before a packed stadium in 1939, where he thanked fans, family and teammates for their support as his career was cut short.

"I may have been given a bad break, but I've got an awful lot to live for," said Gehrig.

The fatal motor neuron disease, which causes progressive paralysis, would take Gehrig's life two years later at age 37. It also took his name, with Lou Gehrig's disease becoming synonymous with ALS.

"It's one of the worst diseases," said Steinman, MD, professor of neurology and neurological sciences, of pediatrics, and of genetics at Stanford Medicine. With few effective treatments, Steinman and other ALS specialists are limited when helping patients as they slowly lose motor control and have trouble walking, chewing and speaking.

"The treatments work a little, which is better than nothing," said Steinman, but he knows better than anyone that it's not nearly good enough. It explains why he is applying lessons learned from a successful multiple sclerosis (MS) study he spearheaded in the early 1990s in hopes that it can lead to a similar drug therapy for ALS patients.

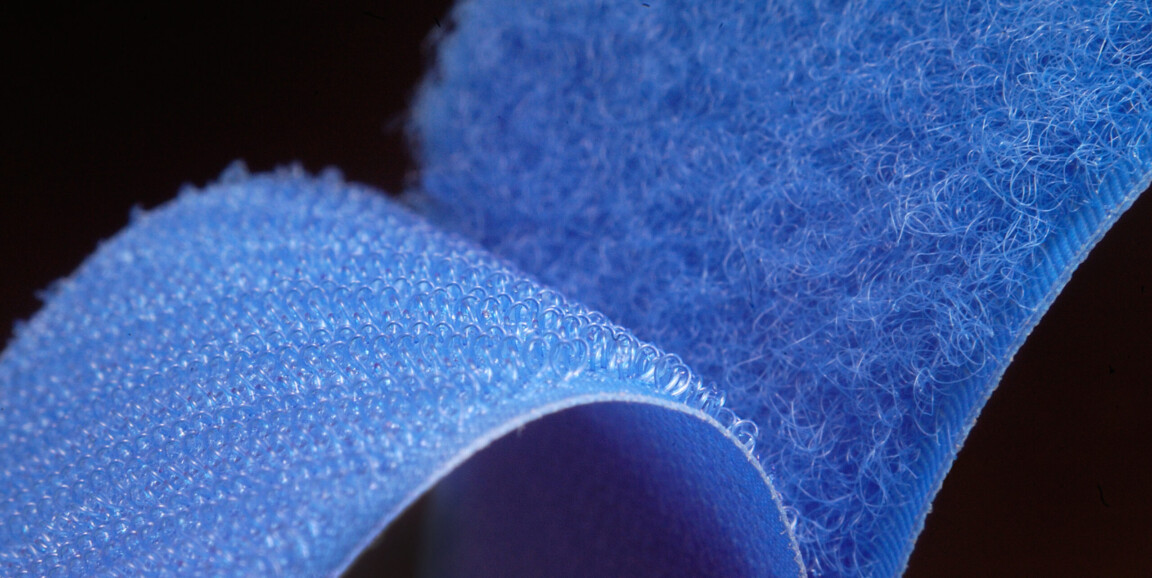

Steinman and his collaborators recently identified a molecule that could be targeted by drug developers to treat ALS. The protein, alpha 5 integrin, is related to another integrin (alpha 4), a type of protein that helps immune cells move and bind to their surroundings like Velcro. It was Steinman's lab that had identified it as a drug target for MS, a neurodegenerative disease where immune cells eat the protective covering around neurons.

That research led to one of the first drug treatments for MS, which slows patients' symptom progression by binding to alpha 4 integrin to block immune cell movement and decrease inflammation. Like MS, ALS also leads to neuron death, possibly through inflammation, which is why the researchers believe this novel treatment could have similarly positive results. Their work on adapting the process for ALS was reported in The Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences on July 31.

"The fact that anti-integrin therapy has worked in other diseases makes me think it's really worth a shot in ALS," said Steinman.

In mice and humans, signs point to alpha 5 integrin

Steinman's lab suspected that alpha 5 integrin, which helps cells bind to their surroundings in the body, was involved in the progression of ALS after they found the protein was expressed in immune cells of mice that were genetically engineered to have ALS-like symptoms. The levels of alpha 5 integrin increased in the immune cells as the mice exhibited more ALS-like symptoms. Steinman knew that rogue immune cells in the brain and body attack motor neurons during ALS, causing the cells to wither and die, and he was curious if alpha 5 integrin might somehow be behind that process.

"We wondered if alpha 5 integrin might help immune cells eat motor neurons," said Steinman.

In ALS, patients selectively lose neurons in their motor pathways, while their sensory pathways are preserved. In human autopsy tissue, this looks like "crater-like structures in areas where there once were motor neurons," Steinman said.

He asked collaborators at the Mayo Clinic to look at where alpha 5 integrin proteins were present in autopsy tissue samples from 132 ALS patients. By staining the human tissue with certain dyes, Steinman's collaborators found more alpha 5 integrin in motor pathways from the brain and spinal cord of ALS patients of different demographics, treatment plans and disease types - compared to patients who did not have ALS. They also saw that alpha 5 integrin selectively lingered in motor pathways, but not sensory pathways in ALS patient tissue.

"It was absolutely stunning," said Steinman. "Alpha 5 integrin is only where the motor neurons are and in the tracts that carry the motor nerves. In other words, alpha 5 integrin is only where the disease is."

Steinman's collaborators also showed that levels of immune cells containing alpha 5 integrin were higher near damaged motor neurons in the brains of deceased ALS patients.

Steinman was curious if a drug blocking alpha 5 integrin would address symptoms in mouse models of ALS. His lab found that the drug, which binds to the integrin, improved motor function, perhaps by hampering their immune cell's ability to move and engulf motor neurons.

"That was thrilling" Steinman said, "Seeing the night and day difference in mice, I thought, 'This could be the anti-integrin drug that works against a horrible disease.'"

The drug largely doesn't cross the blood brain barrier, meaning that only trace amounts of antibody target alpha 5 integrin in immune cells in the brain or spinal cord. But it could reach other immune cells throughout the body, reducing inflammation and protecting motor nerves outside of the spine, which could slow disease progression. Steinman hopes his team can help design a version of the drug that can more effectively cross the blood brain barrier, preventing motor neuron death in the brain as well, and thus possibly stop disease progression entirely.

Still, the drug in its current form might hold promise for humans, Steinman said, and he and collaborators are working toward next steps to test it in clinical trials.

"With this research, we finally reached first base, and we're actually running pretty fast to try to move this to second base," Steinman said. "We might get disappointed. But on the other hand, I've seen things like this work amazingly well."

Photo by curto