Meghana Guduru is a computer vision engineer who works with virtual reality and artificial intelligence systems at Meta. She wasn't expecting to have much interaction with either during her lengthy stay at Stanford Hospital after a bicycle accident. That is until Brian R. Smith, a medical student and research fellow at Stanford Medicine, toted a laptop into her room and helped her create some cute, AI-generated bunny rabbits.

Smith and other researchers with Stanford Medicine are helping patients use AI image-generation software as part of a unique study. The goal of the Portrait Project, created by the Stanford Medicine and the Muse program, is to quantify how creating art aids patients in their recovery.

"There can be a lot of nervousness and uncertainty around AI in medicine, but this is one manifestation that I think people can feel comfortable with," Smith said.

Smith's visit with Guduru started with a series of questions. He asked her what kinds of thoughts make her feel happy. Guduru said she likes to think about bunnies because her 2-year-old daughter, Medha, loves them. Medha has a wild imagination, Guduru said, recounting one of her extemporaneous stories of a bunny falling into a toilet and needing to be rescued by its mother. Guduru also spoke of her own fondness for spending time in her backyard garden and her love of baby deer.

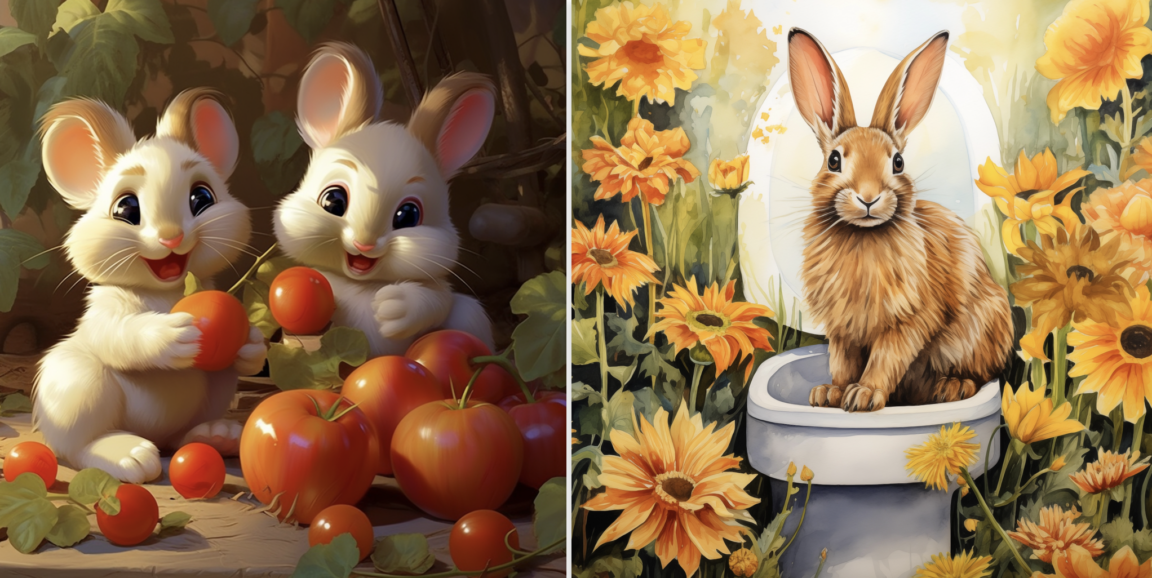

Smith entered Guduru's answers into an AI image-generating program called Midjourney which responded with a painterly image of a rabbit sitting on a toilet, a fantastical rendering of hybrid deer bunnies and two cutesy cartoon bunnies eating tomatoes in a garden. Though they were a bit idiosyncratic, Guduru chuckled and was visibly cheered by the results.

"Cute," she said. "It would make my daughter happy."

Creating connections

The inspiration for the Portrait Project study: a desire to foster more human connection in hospital settings. It was originally imagined as a project that would involve only traditional arts like drawing and painting, but many patients are not well enough to effectively manipulate art tools, and others are simply more comfortable with words. So the study was broadened to include AI image-generating software. Its authors are evaluating both traditional and AI-generated art to learn how each impacts patient recovery.

"Art really allows you to be seen," said Lauren Toomer, faculty director of visual arts for Medicine and the Muse and co-author of the study. "That's valuable for people, especially patients who at times feel like they're just going through the system and have no agency. Art provides a sense of control and relieves anxiety."

Toomer works with patients who wish to create traditional art. She says that, at first, many patients seem only half-engaged, claiming limited artistic skill. Toomer suggests to such patients that they collaborate with her on a painting or drawing, and oftentimes the patient completely takes over the project. Toomer recalls one of her favorite participants, a retired man who expressed minimal interest in the project because he was told as a child that he was no good at art. Toomer got the patient started on a landscape painting.

"By the end of the session we were looking up art stores so when he left the hospital he could buy some materials," Toomer said. "He had this mindset that he wasn't creative, but it took only a moment to show him otherwise. I hope he's still out there creating art."

Smith and Toomer don't need to be convinced of the healing potential of the arts, but many in the health sector require empirical data before embracing new supplemental treatments.

"People in the medical humanities space already understand how art can be helpful in patient recovery, but a lot of medicine is really data- and finance-driven," Smith said. "My hope is that the results of this project will justify standardizing it in some way for the people who would benefit from it."

Taking measurements

The study facilitators collect patient blood pressure measurements before and after they create art. They also have patients fill out surveys regarding their mood, overall sense of wellness and pain level. Initial surveys of this pilot study of 50 patients reinforce the authors' thesis that the process is helping them feel better. Toomer even reports anecdotal evidence of physical improvement in patients with mobility problems.

While the empirical data is important, it's not the main incentive for Smith, who's more interested in the novel opportunities the project affords for human connection between clinicians and patients. When Guduru -- who has more than a passing interest in AI -- challenged Smith on how he would differentiate his AI study to cut through the noise, Smith responded that he didn't really care about that.

"It's not about that," he said. "It's about the conversations like this, and it's a lot of fun -- piggybacking off people's creativity."

Which can lead to therapeutic results. Smith recalled one patient who worked with Toomer on an AI-generated image. The patient initially had no memory of the car accident that landed them in the hospital. Toomer used Midjourney to help the patient create an image inspired by the accident.

The patient created a menacing, elk-like creature with headlights for eyes, standing on a slick road in heavy traffic. Though the ominous beast was clearly symbolic, the process helped the patient recover a few scattered memories of the incident, then created more optimistic, forward-looking images of their recovery. Smith suggests that psychologists and therapists could use tools like Midjourney to better support emotional health.

"There's so much potential," Smith said. "I'm excited to explore how we can humanize the often-dehumanizing experience of the hospital."