While supporting actors are often overlooked, without their contribution, a story's main characters would lose context and resort to isolated monologues.

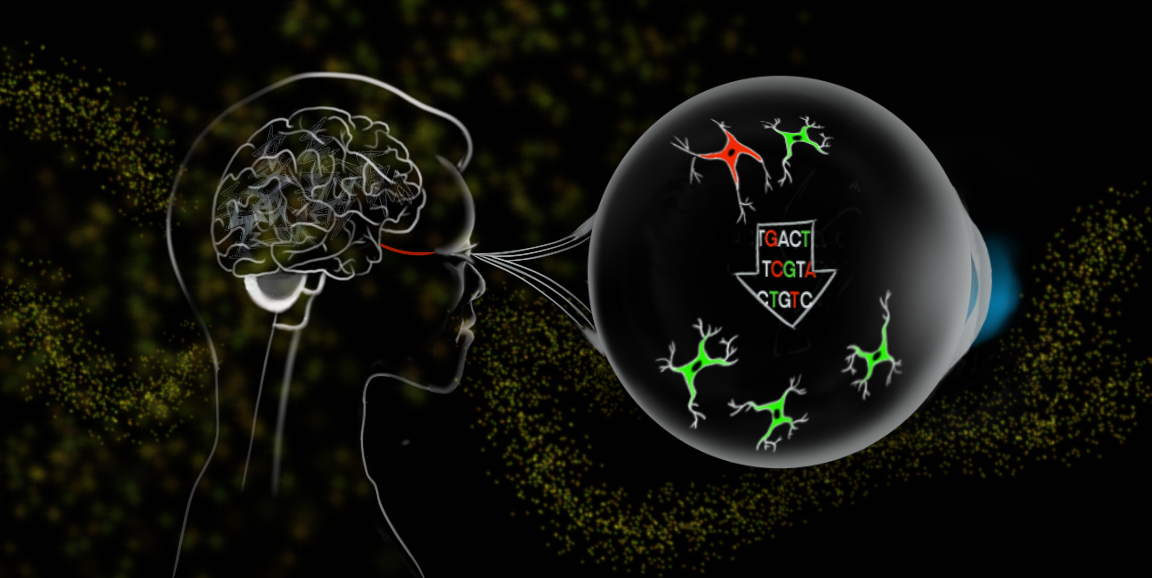

The same is true for neurons -- the top-billing stars of cognition -- when firing in the brain. Without cells called glia, which form the bulk of brain matter, neurons would stop communicating with each other, as seen in neurodegeneration. These supporting glial cells play countless critical roles in the nervous system such as maintaining the chemical environment of neurons and modulating their activity.

Although neurons still rightfully garner A-lister attention when it comes to developing brain therapies, Jeffrey Goldberg, MD, PhD, professor and chair of ophthalmology and the Blumenkranz Smead Professor, believes a young, underexplored class of therapies called gliotherapeutics, which target and harness glia, will ultimately provide important new directions for treatment.

In a paper published in Nature Feb. 12, Goldberg and his colleagues describe an early application for the treatment of optic neuropathies, diseases that damage the nerve at the back of the eye. Glaucoma is the most common of them and is the main contributor to irreversible blindness globally.

The team's technique -- which hasn't yet been tested in humans -- uses drugs or gene therapy (delivering DNA into cells to express or suppress gene activity) to encourage glial cells that protect neurons from injury to proliferate and, hopefully, prevent further damage.

The fact that so much of neurodegeneration is controlled by the glial cells, gives me high confidence that one day gliotherapeutics will prove valuable to patients.

Jeffrey Goldberg

"There still has to be a lot of preclinical validation before we move this into human testing," said Goldberg. "But the fact that so much of neurodegeneration is controlled by the glial cells, gives me high confidence that one day gliotherapeutics will prove valuable to patients."

Goldberg also anticipates that gliotherapeutics won't be limited to eye disease, with potential applications throughout the central nervous system for injuries and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's. In a recent conversation, he talked about movement toward gliotherapeutics, this nascent field's development, and why researchers believe these will be key for treating brain injury and neurodegeneration.

Historically, why have neurons been the focus of treatment and why explore glia instead?

Physicians see a lotof traumatic brain injury, nerve injury and neurodegenerative diseases of the brain, spinal cord and visual system, which together make up the central nervous system. For decades, the field has been focused on developing therapies for neurons, but we've seen limited success in human trials. The premise of opening a new direction to pursue therapeutics, in this case by targeting the glial cells, may be an exciting outlet to meet that unmet need.

Neurons carry all the data in our nervous system and supporting or restoring their function remains the major goal in treating neurodegeneration. The principle of targeting glia is still in service of saving neurons and getting them to function properly. It's just a newer, indirect pathway. The idea that we could reduce degeneration seen in disease or injury by targeting the glia is the premise that we're chasing after here.

You study a type of glia called astrocytes in this paper. Why are they important?

Astrocytes help neurons process incoming signals; they keep synapses (junctions between neurons) functioning properly, and they maintain metabolism in the brain and nervous system. But there's a lot left to understand about astrocytes and how they interact with each other and with neurons.

After injury or in degenerative diseases, astrocytes are quick to react, and much of the research has pointed to their negative effects. They recruit damaging immune cells, shut down the connections between neurons, and even kill the neurons directly. But it turns out, not all astrocytes are bad; there are good ones, too. In healthy people, good astrocytes maintain a proper environment for neurons and, in injured patients, wall off the injured area and make a glial scar so that the injured area doesn't spread.

New data in this paper offer a clearer understanding of how good and bad astrocytes can interact. We've now discovered that one of the jobs of the good astrocytes is to suppress specific types of bad glial cells that invade after injury or during disease and contribute to neuron death.

How would you treat glaucoma with glial-targeted therapy?

Our goal is to increase the proliferation of good astrocytes, to help control the bad ones.

In the study, we discovered a new way to use gene therapy to target the optic nerve head -- where the optic nerve meets the eyeball which becomes damaged in glaucoma and other optic neuropathies. We used a virus to deliver genes specifically to the astrocytes in this region. Those genes altered the level of a molecule called cyclic AMP, which increases proliferation of these good astrocytes, helping them to overtake the bad ones. When the bad glial cells were stopped, that increased the survival of the retinal ganglion cells, which are the neurons that degenerate in optic nerve diseases like glaucoma.

What are the potential implications for patients with these drugs?

The goal of gliotherapeutics includes slowing down the disease or spread of the injury. If we could give patients a gene therapy shot -- developed based on our findings in the paper -- and get their sick neurons to work more effectively, improving their function, that would be a fantastic benefit. Targeting glial cells could also promote regeneration in the visual system, with the potential to restore vision in patients.

The same glial cells and processes are likely present throughout the brain and relevant to other diseases of the nervous system. We only studied the optic nerve in our latest paper, but our findings may be more broadly applicable to promote restoration of damaged neurons throughout the central nervous system. This remains to be tested, and we look forward to carrying these critical next steps forward.

Main image: Emily Moskal