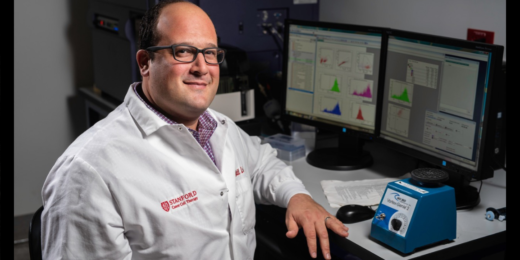

In the lab of Katherine Ferrara, PhD, bubbles spell trouble for cancer cells in mice -- and maybe one day for humans, too.

Specifically, Ferrara, a Stanford Medicine professor of radiology, is using "microbubbles" to damage the structure of cancer cells and cause them to die. The tiny gas-filled spheres are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and are typically used to enhance vasculature imaging in patients. However, Ferrara and her team have repurposed them for a new type of targeted cancer therapy guided by ultrasound.

The new treatment platform is designed to deliver a one-two punch. First, the microbubbles attack cancer cells, then an additional therapeutic agent, such as a gene, beckons immune cells to further pummel the tumor.

Tali Ilovitsh, PhD, a former Stanford postdoctoral scholar and current assistant professor at Tel Aviv University, led the study.

"What's unique about this approach is that we're eliminating a large fraction of tumor cells -- but through this agent, we're also causing the remaining tumor cells to essentially initiate their own demise by recruiting immune cells to the tumor," she told me.

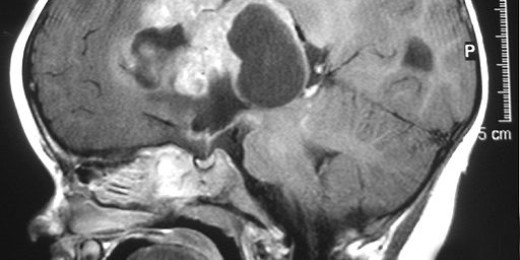

Here's how it works: microbubbles, which are individually smaller than a single cell, are injected directly into a tumor, along with the therapeutic agent. The microbubbles attach to the surface of the tumor cells through a tumor-specific coating. The researchers then use pulses of ultrasound waves to rapidly expand and contract the microbubbles, visually tracking the microbubble location in the tumor with special technology.

The researchers then "tune" the ultrasound to a lower frequency, causing the oscillating microbubbles to act more like a drill. They bore into the cell's surface to form pores -- a perfect inroad for the therapeutic molecule. The agent, in this case a gene, enters the cancer cell and causes it to produce a chemical signal; that signal attracts immune cells and -- ideally -- wipes out the rest of the tumor.

"By having immune cells recruited to the tumor's local region, we seek to teach the immune cells about what the cancer looks like and facilitate the immune cells' ability to kill the cancer systemically," Ferrara said.

There's little risk of microbubbles causing harm to other healthy regions of the body, she told me. Most microbubbles remain near where they are injected, and even if a few stragglers float away, no harm will come of it. To be destructive, microbubbles must be hit with a specific frequency and intensity of ultrasound.

So far, the researchers have tested their microbubble treatment on cancer cells in a dish and in mouse models of breast cancer. The results look promising, Ferrara said. With the treatment, the cancer significantly regressed, and 16% of the mice survived through the end of the six-month study without tumor recurrence. Without the treatment, none of the mice survived. Additionally, compared to mice that received no treatment, the team saw a sevenfold increase in immune cells within a treated tumor, and a fivefold and threefold reduction in local and distant tumor growth, respectively.

As encouraging as these results seem, the microbubble treatment is still not ready for use in humans, Ferrara told me. Currently, she and her team are searching for the therapeutic agent that will be the most effective in recruiting immune cells.

"This treatment is something that you could easily administer on a repeated basis without systemic toxicity," Ferrara said. "Right now, we're focused on finding the best combination of therapeutic molecules to influence immune cell recruitment and initiate a powerful immune response."

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon