Ammonia is usually a harmless byproduct of digestion that is passed out of the body through urine. But some people with liver disease and certain genetic conditions do not effectively metabolize ammonia, creating a buildup that can cause various physical and mental symptoms. In newborns with metabolic conditions, elevated blood ammonia levels can cause brain damage within hours.

After treating a patient with an unusual ammonia metabolism problem, Gilbert Chu, MD, PhD, professor of medicine (oncology) and of biochemistry at Stanford Medicine, assembled a team of researchers to reimagine the cumbersome process of ammonia blood testing.

The researchers have since developed a prototype of a portable device that people could use to test ammonia levels at home. A paper describing their work was posted online in ACS Sensors, and they are preparing for studies that could make them eligible for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval.

Mystery becomes motivation

The development began when a patient of Chu's arrived at the hospital. Her health had been deteriorating for weeks; she was delirious and unable to walk. A blood plasma test -- one among a series of tests Chu used to find some explanation for her symptoms -- showed highly elevated levels of ammonia in her blood.

"The only thing that I could think of was: Could it have been my fault?" Chu said in a Stanford News Service article about this research. "I looked at her chemotherapy, which she had been taking. It was an oral form of fluorouracil, one of the oldest chemotherapy drugs. This was not a known side effect, but the timeline matched her symptoms."

Chu then discovered that the woman had an anatomical anomaly and gene mutations that reduced her ammonia metabolism -- an issue that her chemotherapy drug exacerbated.

Solving the problem was relatively simple; but in working on it, Chu realized how difficult it is for people to monitor their own ammonia levels. Testing requires that blood be drawn from a vein, put on ice and delivered quickly to a lab for analysis. The process was so finicky that, in the course of treating his patient, blood draws Chu took were rejected twice.

Producing a prototype

Motivated to create an easy-to-use sensor for measuring blood ammonia -- like a glucometer for measuring blood sugar -- Chu broached the idea with faculty members at a Stanford ChEM-H dinner.

It just so happened that a fellow dinner guest, Matthew Kanan, PhD, associate professor of chemistry, had a graduate student who was working on a sensor for measuring ammonia in any liquid.

Together the team -- including Chu, Kanan, the graduate student, Thomas Veltman, Natalia Gomez-Ospina, MD, PhD, and research associate Chun Tsai -- produced a prototype of the device.

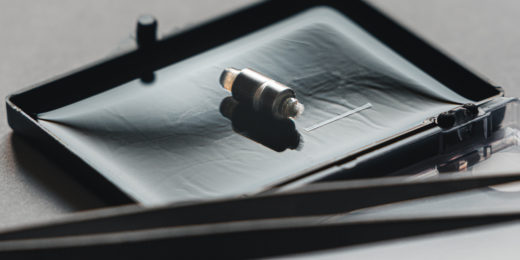

The sensor, which is about the size of a TV remote, is repurposed from an existing technology used for sensing gaseous ammonia in industrial settings. It's paired with test stripes that Veltman developed. Dabbed with capillary blood -- which can be obtained from a finger or earlobe stick -- the strip uses a chemical process to liberate the ammonia from the blood. The device measures and reports the ammonia level in less than a minute.

The researchers took care to optimize the design for mass production and affordability, and founded a company focused on the technology.

"I've spoken with families who have children with this condition about having this kind of device, and it makes them emotional because the consequences of not getting ammonia checked accurately and quickly are so severe," said Gomez-Ospina, who is an assistant professor of pediatrics. "For these families, it could be life-changing."

Image courtesy of Gilbert Chu