Every year, heart disease is responsible for 19 million deaths worldwide. That's nearly twice the number of cancer deaths, yet people's perceptions of heart disease and cancer are remarkably different.

The majority of Americans aged 40 to 75 go for regular cancer screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and if they are diagnosed, are usually diligent about following the recommended treatments. Many are aware of the genetic cancer risk in their families. Similar screenings, effective medications and genetic tests are available for heart disease, but fewer patients know about them and fewer physicians propose them.

Michael V. McConnell, MD, a preventive cardiologist and clinical professor of medicine at Stanford Medicine, has encountered this less serious attitude toward heart disease both in his patients and his own family. In his new book, Fight Heart Disease Like Cancer, McConnell explains the biological parallels between a cancerous tumor and the plaque that grows in blood vessels -- the main cause of heart disease -- and why we should take a similar approach in preventing and treating the two conditions.

It's much more like a growing tumor in our heart vessels that can become malignant and needs serious care.

Michael McConnell

"We continue to think of heart disease as a simple problem of clogged pipes that need opening," he writes in the book. "Rather, it's much more like a growing tumor in our heart vessels that can become malignant and needs serious care -- and straight talk -- to be stopped."

We asked McConnell to share some straight talk on this more proactive approach to fighting heart disease.

How did you come to the realization that we need to fight heart disease more like cancer?

It came from both personal and professional experiences. Part of what motivated me to write the book is, unfortunately, what happened to my father-in-law. He was a scientist and expert on early cancer detection. He was feeling fine one day, gave a lecture, and was on his way to a celebratory dinner, but never made it. He had a heart attack that blocked the blood flow to his heart, and his heart stopped. My daughters were only 10 and 13 and I don't want this to happen to other families.

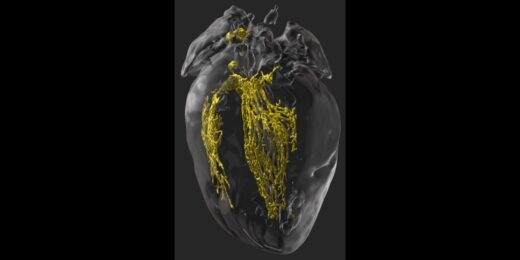

Professionally, we've known for a long time that plaque -- what was originally called atheroma, Greek for "fatty tumor" -- can build up silently in the walls of our heart arteries. But the science has now made very clear that these plaque "tumors" become biologically active, with cells dividing, attracting inflammatory cells and growing for quite some time inside the artery wall without causing symptoms. The plaque can burst and cause a blood clot. You can go from no blockage to a complete blockage very quickly.

While we have balloons and stents and bypass surgery to treat severely blocked arteries, waiting for this late stage of heart disease is often too late. Many people still die before they get to the hospital.

The message I want to convey is that it's much more of a biological disease, not just one of plumbing. We need to look for earlier growths and biological activity, analogous to how oncologists look for cancers. We can do a lot to stop it and reverse it if we catch it early.

How does plaque grow in the arteries?

Typically, plaque starts with fat infiltrating the walls of the artery. The big three "growth factors" are high cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugar (as in diabetes). Then our immune system sends in macrophages, which are cells intended to gobble up material and get rid of it. They ingest a lot of the fat, but instead of clearing it out, the macrophages die in the blood vessel wall; those dead cells keep triggering more inflammation. Those are the factors that make plaque more "malignant" and prone to burst.

Then there's the iceberg problem. The plaque can grow very large inside the artery wall, yet only a little bit protrudes into where the blood is flowing.

Michael McConnell

Then there's the iceberg problem. The plaque can grow very large inside the artery wall, yet only a little bit protrudes into where the blood is flowing, so you won't have any symptoms. On an angiogram, which images blood flow, you would see only the tip of the iceberg.

This silent plaque can suddenly crack, tear or burst and then the blood flowing over the plaque forms a blood clot to seal up the problem. A study found that clots that cause heart attack usually don't happen where the plaque had been most visible.

You say that no one should be having heart attacks. How do we prevent plaque from growing?

We shouldn't be waiting for late-stage disease because, like my father-in-law, your first symptom may be your last. We really need to look at earlier detection when it's most treatable and reversible.

Noninvasive imaging techniques can see beyond the tip of the iceberg to where plaque is growing inside the walls. The main screening test is called a coronary artery calcium scan, or CAC, an X-ray scan that can detect calcium deposits that develop in plaque. It works much like a mammogram, which looks for calcification in breast cancer tumors.

In addition to a heart-healthy lifestyle, the preventive approach includes lowering your bad cholesterol (LDL) as much as possible with drugs like statins or PCSK9 inhibitors -- what I call our preventive chemotherapy. That can suppress or reverse the biological activity of the plaque. There are also a number of medications in research -- some originally developed for cancer -- that directly tackle inflammation, which can also help make the plaque more benign and less prone to cause a heart attack.

What do you hope people will take away from this book?

Make sure you know your numbers. Work with your doctor to understand your heart disease risk score, now known as PREVENT, which predicts your 10-year and 30-risk of heart attack, stroke and heart failure. Many men in their 50s and women in their 60s, and younger if there's a family history, are going to have high enough risk that warrants either preventive therapy or a screening test, such as a CAC scan, to see if they have plaque buildup.

There are so many more people we could be helping.

Michael McConnell

We have very effective medications, yet only half of U.S. patients who would benefit from cholesterol-lowering medicines are on them. In low- and mid-income countries throughout the world, it's only 8%. There are so many more people we could be helping.

Should we be more concerned about heart disease than we are?

People should definitely appreciate the seriousness of heart disease. I titled one of the chapters "Heart Disease is Like Cancer, Only Worse" because it not only kills more people but it can kill you a lot more quickly.

While I strongly advocate healthy behaviors for prevention for my patients, once you have plaque growing in your heart arteries, a little more physical activity and a little bit better diet aren't going to stop those plaques from growing and bursting and killing you. We have very effective medications to stop or reverse the growth, but you need to approach it more like a growing tumor.

When I've told patients they basically have the equivalent of cancer growing in their heart arteries, that's often had a very profound, visceral impact.

Image: goldyg