Lillie Reed has been raising awareness about gender-based violence and the resulting trauma ever since she began studying public health as an undergraduate at Duke University. But her passion for the work grew from personal experience.

Raised in Greenville, North Carolina, Reed said her first experiences with abuse were at home and that her upbringing showed that the experience of domestic violence goes well beyond the violence. "The fear and anger and other ripple effects that violence creates ... it can feel inescapable," she said. "When you are experiencing domestic violence, even in peaceful moments, it can consume your life ."

While the move two hours west to Durham gave Reed distance from that upbringing, it also exposed her to the larger world where different forms of gender-based violence -- such as sexual assault -- are prevalent. The understanding of a greater need beyond her own helped crystalize an academic and personal mission for Reed: "Violence felt like such a huge, omnipresent problem -- I wanted to do something about it."

Over the past decade, Reed has dedicated her life and academic career to preventing violence and helping victims heal from the resulting trauma.

At Stanford Medicine, Reed, a fifth-year medical student planning to become a child and adolescent psychiatrist, has provided therapy to children with post-traumatic stress disorder in the Stanford Medicine Children's Health Trauma Clinic under the supervision of Dr. Hilit Kletter, PhD. She's also conducted research led by Clea Sarnquist, DrPH, a clinical associate professor of pediatrics, into the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on girls and young women in Western Kenya, and with Dr. Jennifer Newberry, MD, JD, focusing on domestic violence in Santa Clara County Latino communities .

Reed, recipient of a Global Health Medical Student Research Fellowship, is currently in Mexico working with Xinshu She, MD, a Stanford Medicine pediatrician and clinical associate professor in pediatrics and global health, to help develop a mental wellness parenting program for families in migrant shelters at the border.

With International Women's Day approaching on March 8, we took the opportunity to ask Reed about her advocacy for people facing gender-based violence and how becoming a psychiatrist will help shape her future work. This Q&A has been condensed and edited for clarity.

How did you become engaged in working to address gender-based violence?

Violence was omnipresent in my community and normalized in my schools and in my home. But when I was in college, I learned that about 1 in 3 women and 1 in 6 men experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime. And that's not including harassment, emotional, financial, or other types of violence. I began to see gender-based violence as one of the most important and under-attended public health issues of our time.

I also view it as a social justice issue: Violence is about power and control, and groups that have less power and control, including women, are more vulnerable to it. So, for me, this work is a fight not just for health and safety, but for justice and equity.

How do you hope becoming a physician, focusing on psychiatry, will further your efforts to address this issue?

Working in global health, I saw that mental health cannot be separated from people's life context. When I worked on community mental health interventions, what we heard from patients wasn't just, "I'm depressed." It's, "I can't afford my diabetes medication and it's spiking my anxiety." Or, "I'm depressed because my husband is abusing me."

I first planned to pursue psychology, but I was concerned I couldn't address all the physical and social aspects of health I wanted to address. So I shifted to public health and eventually, decided on becoming a physician.

Now, I'm back where I started, and I plan to become a psychiatrist. I've loved all my psychiatry clerkships and the ways I get to show up for my patients as a member of the psychiatry team, but my decision was truly confirmed by my experience working in the pediatric PTSD clinic. You can be a powerful advocate for social justice through psychiatry and community-based psychiatric work, and I want to build that into my career.

I love doing trauma-focused therapy. It's fulfilling to educate young people about trauma and to help them to reduce its impact on their lives.

Lillie Reed

I love doing trauma-focused therapy. It's fulfilling to educate young people about trauma and to help them to reduce its impact on their lives. I think this work feels particularly impactful for me, having gone through my own individual experience of violence and trauma -- and the process of healing from it. I hope I can offer empathy and understanding that comes from a real place.

Is trauma therapy for children effective?

Good trauma-focused therapy is very effective in treating PTSD, and children are especially responsive to the right therapy. I'm still very new to the therapy work, but even in that time, I've seen it myself. I've seen patients as young as 5 or 6 go from having significant symptoms of PTSD to being almost symptom-free in less than a year. It's important that we do treat trauma when it happens -- because evidence shows that chronic trauma symptoms generally don't resolve without treatment.

Talk about the international work you've done.

After college, I worked at the World Health Organization, developing regional and global action plans and trainings focused on mental health and the prevention of violence against women and children. After that, I worked in Malawi and Zambia for several years. I was privileged to do lots of different work during that time, but my favorite job was creating youth empowerment programs to help prevent violence and improve health.

When the pandemic hit, I worked with a team of Kenyan researchers to understand the needs of western Kenya teenagers who had been exposed to or experienced violence, researching how the pandemic affected them. The research, led by Dr. Sarnquist and Dr. Hellen Barsosio , supported by the Marjorie Lozoff Prize, was recently published in Frontiers in Reproductive Health.

Much of my U.S.-based work has been with domestic violence organizations within Latino communities. I became especially interested in working within these communities in part because of my first experiences working as a crisis counselor and patient advocate with Spanish-speaking survivors in Durham, and due to family background. My mom was mostly raised in Panama and some of my family is from Mexico.

You're currently doing work in Mexico -- what does that entail?

I'm working with Dr. She, implementing a parenting skills intervention to try to improve the mental health of parents and young children living in shelters at the border as they await immigration hearings. These children and their parents are living in profoundly stressful situations.

I'm also passionate about the humanities, and love to mix storytelling and art into my work. I received a Stanford University Arts + Justice Grant to work with the community here to create a writing and art program to build coping skills and emotional resilience, and to help kids here feel empowered to tell their stories.

I think that that drive to treat people with compassion and fight for justice -- on an individual and community level -- came out of my experiences, and it definitely still continues to fuel my work in social justice and in violence, and in that intersection, because violence is a social justice issue. I know from my own experience that healing is possible, and I get so much joy in helping others find what healing looks like for them. Learning to reframe your own story, to see yourself as a survivor of trauma, and not as a victim of it, can make a world of difference.

You created a mnemonic to help people advocate for folks in their communities who are gender-based violence victims.

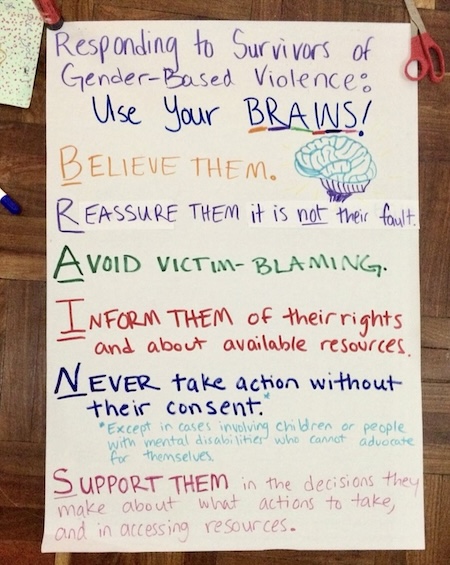

Since I mostly worked with kids in Malawi and Zambia, I wanted to create a succinct, easy-to-remember way to empower them to support gender-based violence survivors. When people hear about how prevalent violence is and realize that their community is affected by this issue, they want to help. Friends and family are often the first responders to violence, and what I've heard from most people is that they feel unsure what to do or say if someone discloses to them. So I created a mnemonic as a guide: BRAINS!

B is for believe them. R is for reassure them that it's not their fault. A is for affirm their feelings and experiences. I is for inform them of their rights and resources. N is for never take action without their consent (except in cases of violence against children or people who lack the capacity to advocate for themselves.). S is for support them in the actions they choose and make space for self-care.

I want community members to see themselves as part of the solution. They can be a huge part of violence prevention and intervention -- particularly in low-resource settings where professional help might be inaccessible. Also, friends and family are often more aware of these situations, and may be more able to help than we are as medical providers.