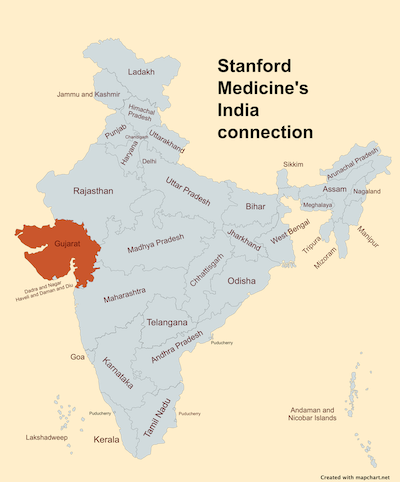

Three first-time mothers dressed in identical pink, floor-length hospital gowns and blue surgical masks sat in a small, windowless hospital conference room in rural Gujarat, a state of 60 million people on India's western coast, roughly half the size of California.

The young women described the experience of having a child in the neonatal intensive care unit at this modern hospital located so far from their homes that they were staying in the mothers' onsite dormitory. One mom had been there for nearly two months.

Speaking in Gujarati, the mothers shared worries about how their families were faring without them back home -- some as far as a three-hour drive away. One talked about the pain of lactation and the others readily agreed. Another said she was angry with God, though, with her baby's health now improving, her faith was starting to rebuild.

By the end of the conversation, all agreed group therapy sessions where NICU moms could talk about how they're feeling, just as they had done that day, would be helpful in relieving stress and alleviating loneliness.

Several Stanford Medicine clinicians were part of that conversation in January and able to ask the mothers questions with the translation help of an Indian psychiatrist.

The doctors had traveled to India as part of a longtime educational collaboration with the Shrimad Rajchandra Hospital and Research Centre (SRHRC) at the invitation of Stanford Medicine neonatologist Nilima Ragavan, MD, a native of India who had helped establish the relationship nearly 10 years earlier. They were invited there in part to help the local clinicians brainstorm how perinatal mental health programs could work in rural India -- where the direct, measurement-based approach of academic psychology may not be appropriate.

"It might be enough to start out with just encouraging people to talk about their emotions," said Stanford child and adolescent psychologist Richard Shaw, MD.

It might be enough to start out with just encouraging people to talk about their emotions.

The January visit to India -- which centered around an annual symposium -- was a byproduct of the medical and cultural exchange between Stanford Medicine, SRHRC, and the government of Gujarat. The goal of the initiative, named Teach To Heal, is to foster the exchange of evidence-based best practices between clinicians from different parts of the globe. The collaboration has led to the Stanford Global Child Health Program approving SRHRC as one of just a few sites around the world where school of medicine pediatric trainees can travel for global health rotations and electives.

The center in India, Ragavan explained, is unique in that it combines acute, comprehensive care -- including a mobile outreach program -- provided at little to no cost, to the nearby rural population made up of tribal and migrant communities.

Five faculty members from the divisions of general pediatrics, pediatric nephrology, child & adolescent psychiatry and one neonatology fellow made up the Stanford Medicine interdisciplinary contingent that accompanied Ragavan to India, traveling for five hours from Mumbai on bumpy and winding roads to reach the center. Each presented at the symposium bringing together doctors, nurses and other health care representatives from India and the U.S. to discuss advances in perinatal medicine.

* * *

One of the primary objectives this year was gauging the appetite for palliative care and perinatal mental health interventions. Historically, mental health has been a taboo topic in India, Ragavan explained. She wasn't sure how discussions of perinatal depression and anxiety would be received, or even if mental health was perceived as a problem among clinicians and families.

"Before trying to impose a solution to a problem," said Shaw, "we needed to figure out whether there was a problem and how it's similar to, or different from, what we see in the U.S."

We needed to figure out whether there was a problem and how it's similar to, or different from, what we see in the U.S.

He observed that guilt may be a universal feeling for NICU moms no matter the location, but also recognized that mental health interventions should originate from Indian clinicians who understand the language, tribal needs and cultural norms.

Local know-how is especially important in India, which is estimated to be the most populous country in the world. UNICEF reports over 25 million babies are born in India each year, whereas U.S. births per year hovers around 3.6 million, according to the most recent census data. While the Indian government recognizes 22 official languages (in addition to English), there are hundreds more unofficial languages and thousands of dialects spoken.

"The key for anybody who's going to do global health work is to collaborate with teams on the ground," Ragavan said.

Ragavan says the collaboration has grown over the last 10 years thanks to a great deal of listening. "The approach was: Let's just start at the grassroots level and then let's build up upon our success," she said.

Atmarpit Dr. Mansiji, the pediatrician who leads the neonatology team at the Indian center and received medical training in both the U.S. and India, said collaborating with Stanford Medicine has been refreshing.

"Nilima actually understood the context of where we are, what we have and what small interventions could make huge differences in outcome," Mansiji said.

For instance, when the center's NICU staff shared a distressing statistic about the mortality rate for babies born elsewhere and brought to the center, an intervention was proposed. In 2018, Ragavan and a team of Stanford Medicine doctors, nurse practitioners, critical care transport nurses and respiratory therapists worked with the center's staff to develop a specialized neonatal transport team and van that has improved outcomes for babies born outside the hospital.

* * *

At the request of the government of Gujarat, Ragavan has scaled up Stanford Medicine's presence in the state and she now regularly communicates with clinicians at other Gujarat hospitals and medical colleges about their needs.

Given the trauma families often experience as a result of having a child in the NICU, it made sense to Ragavan and the core team in India to introduce the topic of perinatal mental health at SRHRC and to the broader community of obstetricians and pediatricians in Gujarat.

Stanford pediatric and perinatal psychologist Celeste Poe, PhD, presented on perinatal mental health disorders at the January symposium and was excited to share her expertise, noting that psychologists working in NICUs are still rare, even in the U.S.

Families benefit when everyone they encounter in the hospital shares the importance of mental health, especially in the perinatal period.

"Families benefit when everyone they encounter in the hospital shares the importance of mental health, especially in the perinatal period," she said, adding that just asking families how they're doing can go a long way.

In India, like the U.S., there is often an expectation that moms are selfless nurturers who put themselves last. As Poe spoke with Indian clinicians about addressing "self-care" with new moms, the clinicians shared that "self care" connotated selfishness.

When she reframed "self care" to focus on the benefits for both moms and babies - for example, moms getting adequate nutrition or sleep to be able to better care for their babies - there was wider agreement about its applicability. "That was an enlightening conversation about how to approach some of those mental health aspects in a culturally sensitive way and adapt terminology," Poe said.

That was an enlightening conversation about how to approach some of those mental health aspects in a culturally sensitive way and adapt terminology.

Ragavan is pleased clinicians in India were receptive to addressing perinatal mental health and looks forward to further meaningful collaboration.

In reflecting on what continues to drive the near decade-long exchange, Ragavan described a shared mission to make sure that evidence-based care is equitably and widely disseminated across Gujarat and beyond. What does she see when she visits? Clinicians from both the U.S. and India enthusiastic about making holistic improvements to care.

"Both sides feel so positive about the collaboration," Ragavan said. "The team came back to California thinking what we received from our time in India is more than what we gave."