For years, Stanford University chemical engineer Zhenan Bao, PhD, and her lab have worked on a plastic, skin-like material that can detect small changes in pressure and report those as an electrical signal. They’ve investigated how this sensor might give a sense of touch to protheses and to robots but the researchers continue to look for other possible applications.

In the midst of searching for potential uses in the medical field, Clementine Boutry, PhD, who at the time was a postdoc in the Bao lab, happened to meet Anaïs Legrand, who was a postdoc in surgery, and the two initiated a powerful collaboration between Bao’s lab and the labs of Paige Fox, MD, PhD, assistant professor of surgery, and James Chang, MD, chief of plastic and reconstructive surgery.

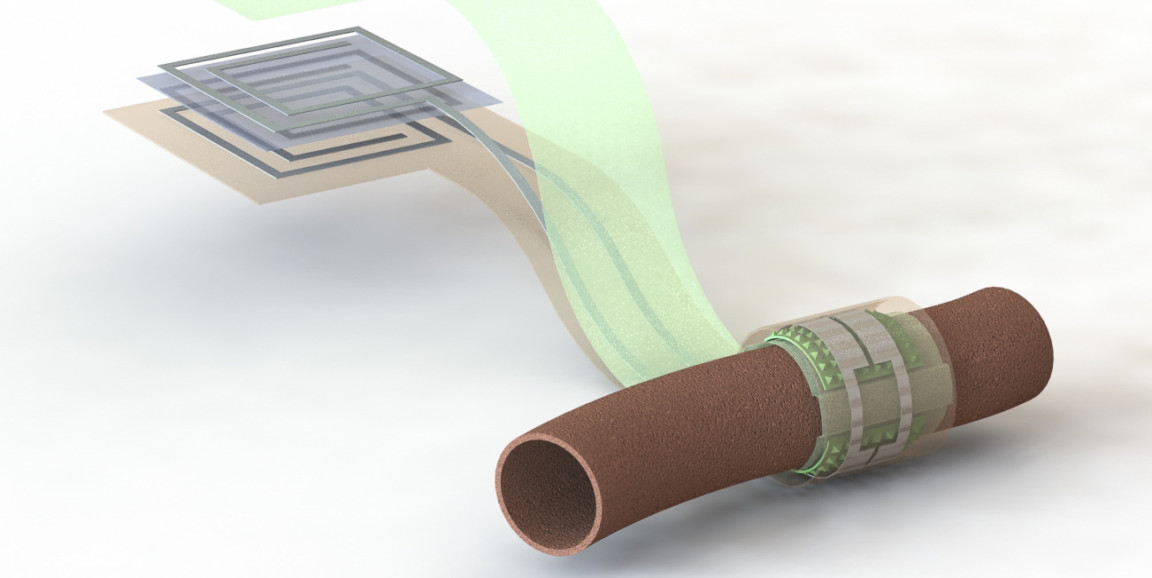

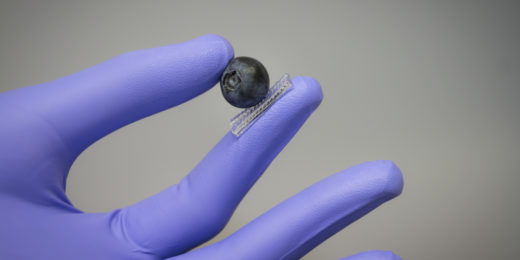

Together, these researchers have developed a new kind of implantable, biodegradable, wireless and battery-free blood flow sensor that could be used to remotely monitor the success of surgery on blood vessels. Once wrapped around a blood vessel, changing pressure within the vessel changes the shape of the sensor, which alters its ability to store electric charge. To solicit a measurement from the sensor, a device held outside the skin pings the antenna attached to the sensor (much like an ID card reader getting information from a card). The idea is that a person’s doctor can monitor their blood flow remotely, possibly through reports from a wearable or app, and then the sensor biodegrades after it’s no longer needed.

In a Stanford News press release about the device, Fox outlined the potential impact of this technology:

Measurement of blood flow is critical in many medical specialties, so a wireless biodegradable sensor could impact multiple fields including vascular, transplant, reconstructive and cardiac surgery. As we attempt to care for patients throughout the Bay Area, Central Valley, California and beyond, this is a technology that will allow us to extend our care without requiring face-to-face visits or tests.

The researchers successfully tested the sensor by measuring pulsating air flow through an artificial vessel and blood flow through the artery of a rat. So far, they’ve only reported results for complete blockages of flow but saw indications that future versions of this sensor could identify smaller fluctuations as well. They plan to continue refining and testing their design with an open mind about its potential applications.

As Bao told Stanford News:

Using sensors to allow a patient to discover problems early on is becoming a trend for precision health. It will require people from engineering, from medical school and data people to really work together, and the problems they can address are very exciting.

Image of sensor by Levent Beker