Unconventional Paths: Stories of Stanford Medicine faculty, researchers and physicians whose journeys into medicine followed nontraditional routes

As a mechanical engineering graduate student, Alison Marsden studied how to make submarines more stealthy.

Moving through the ocean, submarines make sounds that can reveal their location. While earning her PhD at Stanford University in the early 2000s, Marsden conducted U.S. Navy-funded research that used sophisticated computer modeling to optimize the shape of the submarines' hydrofoils, which work like airplane wings, generating lift and stabilizing the submarine underwater. Her aim: to minimize telltale churning sounds and enable the vessels to cruise subsurface, undetected.

Marsden has always loved the science of fluid mechanics and she enjoyed the technical aspects of her submarine research, but she knew national defense work would not sustain her interest long-term. In 2005, as she neared the end of her PhD work, she looked for a postdoc job in a new research realm that would use her skills at designing solids to interact optimally with nearby liquids.

She hoped for a research field that allowed her to follow her heart.

That field turned out to center on hearts themselves.

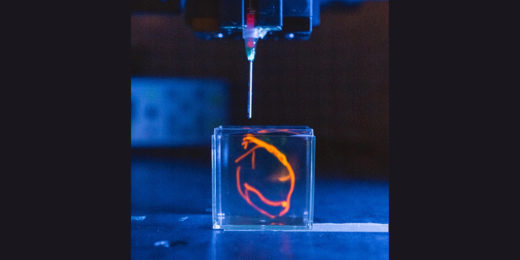

Now, Marsden, PhD, is the Douglass M. and Nola Leishman Professor of Cardiovascular Diseases at Stanford Medicine and a professor of pediatrics and of bioengineering. She leads a lab that models how blood flows through the hearts of babies born with heart defects, as well as children and adults with cardiovascular disease.

"We take a patient's medical imaging data, process the images to reconstruct their anatomy, and end up with a 3D model in the computer of that patient's blood vessels," Marsden said. "We can try out different scenarios for surgical repair and run simulations to compare option A versus option B."

In other words, Marsden's team helps surgeons design repairs that are personalized for each patient's heart.

Starting from little science projects

Marsden grew up in Berkeley and Marin County, California, enjoying a childhood full of "little science projects." Her math-professor dad helped her chart the weather. Her mom, a teacher, photographer and naturalist, organized trips to national parks and signed her up for classes at the local science museum. Her stepdad explained the difference between science and engineering, telling her, "Science is about answering questions and engineering is more about creating or building things," Marsden recalled.

As an undergraduate in mechanical engineering at Princeton University, Marsden became hooked on fluid dynamics, the physics of liquids and gasses in motion, and was intrigued by how this applied to real-world problems. One of her earliest research projects focused on how fish swim.

In graduate school, she built computer models showing how turbulent fluids behaved as they passed solid objects. Viscous fluids move at varying speeds depending on how close they are to a nearby solid. This creates phenomena such as a boat's churned-up wake, the lift of a fast-moving airplane wing, or sometimes, an unexpected blood-pressure change inside a diseased blood vessel.

The latter was a research focus for Charles Taylor, PhD, whom Marsden approached about a postdoctoral job in early 2005. Taylor, then an associate professor of bioengineering and of surgery at Stanford Medicine, led a lab making patient-specific computer models of blood flow and blood pressure. It's no easy task to figure out how the equations that describe the motion of viscous fluids will play out in each artery or vein.

"Especially in complex geometry like a curving blood vessel, we can't solve these equations by hand, so we farm it out to a large supercomputer," Marsden said. When she met Taylor, they realized that her computer-modeling skills honed on submarines could help hearts, too.

"He was really excited about technical skills I could bring to the lab, and I was excited about the applications," said Marsden. "He basically hired me on the spot."

High-pressure predictions

Taylor introduced Marsden to Jeffrey Feinstein, MD, director of the Center for Pulmonary Vascular disease at Stanford Medicine Children's Health, with whom she still collaborates.

To plan how to repair a congenital heart defect, cardiac surgeons typically look at patients' medical imaging data and, guided by their clinical experience, visualize or sketch the best fix. But not even experienced surgeons can always predict how a cardiac repair will affect each patient over time. This is especially true with patients who have severe defects, such having only one pumping chamber in the heart instead of two, or when there's an unusual combination of heart problems.

In pediatric cardiology, one of Marsden's main areas of research, surgeons contend with big differences in anatomy from child to child, as well as the challenges of planning for growth. "It's not always intuitive what will happen in the years that follow surgery," Marsden said.

A less-than-ideal heart repair can ultimately lead to dangerously high blood pressure in the small, relatively fragile blood vessels of the lungs.

That's where computer modeling comes in. It doesn't replace a surgeon's expertise, but it gives them an edge and allows them to pressure test their surgical plan.

Some of the models developed in Marsden's lab have also helped doctors identify cases that won't benefit from certain go-to heart fixes, such stenting, which opens narrowed blood vessels. In those instances, the modeling saves patients from unnecessary procedures.

And, perhaps most important, "Modeling gives us a sand box to play with high-risk ideas without putting any patients at risk," Marsden said.

For instance, over the first two to three years of life, babies born with a single ventricle or pumping chamber in the heart, instead of the usual two, receive a series of three open-heart surgeries to reroute circulation through their heart and lungs. The final surgery, a Fontan procedure, has traditionally involved connecting two major blood vessels using a T-shaped junction.

But Marsden's team proposed a different option: a Y-shaped graft. Using modeling, Marsden showed the Y-replacement would result in a more balanced distribution of blood flow between the left and right lungs in the long run. The modeling provided the basis for a successful pilot of the new technique in children.

The team is also creating models of an even bolder idea that they have yet to test in humans: combining the first two surgeries for single-ventricle patients into one procedure.

"That's a good example of a situation where we can use modeling to test a new approach in a very low-risk and rapid way," Marsden said.

Engineered for growth

After almost 20 years of engineering blood vessels, would Marsden ever consider going back to submarines?

"I can't imagine going back," she said. "I love working with medical doctors. I'm a PhD and only treat patients in the computer, and every time I talk to our clinical collaborators I learn new things. They have really amazing perspective, which gives us lots of new ideas."

Marsden loves that her team's work can make an immediate difference for a baby, child or adult. She also likes that engineering a living system is less straightforward than building better submarine parts.

"A blood vessel can sense mechanical forces such as changes in blood pressure, and the vessel wall responds by changing and growing over time. How do you model that process?" Marsden said. "How do you know the model is correct and accounts for things happening at multiple scales: the scale of cells, the scale of whole blood vessels or, at a tinier scale, genes? It makes these biological problems challenging and fascinating."

There's a huge untapped need in many areas of medicine for a more quantitative approach, Marsden said. "We're very used to using computer simulation and modeling in traditional engineering disciplines such as automotive engineering, aerospace and weather prediction. But we've barely scratched the surface in medicine and biology."

Read more Unconventional Paths stories here.

Image of blood vessels around the heart courtesy of the Cardiovascular Biomechanics Computation Lab.